The first images of the giant black holes at the centers of M87 and the Milky Way were produced by a planet-spanning network of radio observatories known as the Event Horizon Telescope in 2019 and 2022, respectively. They showed a bright ring of hot orbiting gas encircling a circular zone of darkness.

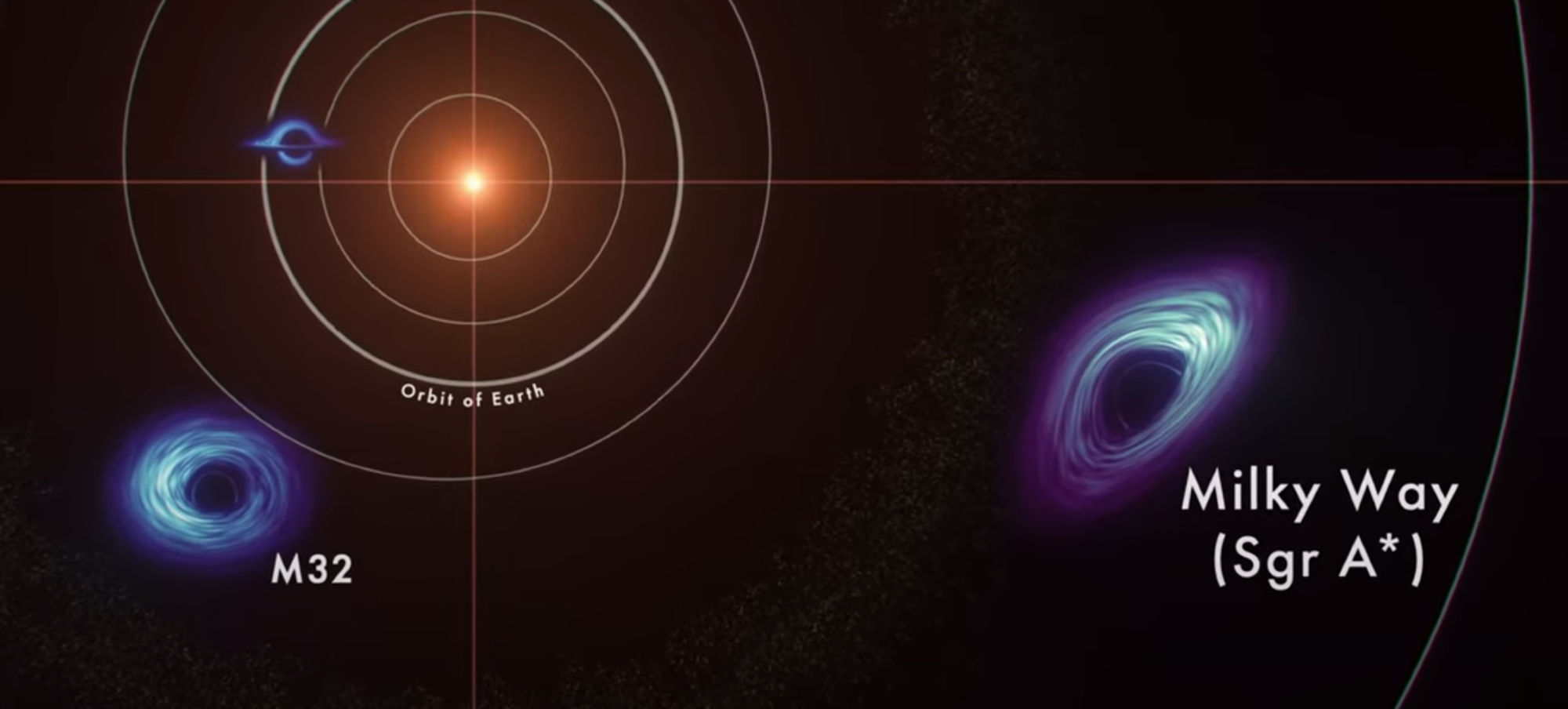

This frame from NASA’s new animation compares the sizes of three supermassive black holes in relation to planetary orbits in our solar system. At top left, unlabeled, is the black hole at the center of the Circinus galaxy. Below it lies the giant black hole in galaxy M32. And at right is the more massive black hole at the heart of our own Milky Way galaxy. Image Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

Direct measurements, many made with the help of the Hubble Space Telescope, confirm the presence of more than 100 supermassive black holes. How do they get so big? When galaxies collide, their central black holes eventually may merge together too.

Jeremy Schnittman, Theorist, Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Any light that crosses the event horizon—the black hole’s point of no return—turns out to be trapped forever, and any light passing close to it has been redirected by the intense gravity of the black hole. Collectively, such effects produce a so-called “shadow” around twice the size of the actual event horizon of the black hole.

A new NASA animation displays around 10 supersized black holes that engage center stage in their host galaxies, such as the Milky Way and M87, scaled by the sizes of their shadows. Beginning near the Sun, the camera steadily backs off to make a comparison of the ever-larger black holes to various structures in the solar system.

First up is 1601+3113, a dwarf galaxy hosting a black hole packed with the mass of nearly 100,000 Suns. The matter is subjected to such compression that even the shadow of the black hole is smaller compared to the Sun.

At the heart of our galaxy, the black hole known as Sagittarius A is present, which boasts the weight of 4.3 million Suns depending on long-term tracking of stars in orbit around it. Its shadow diameter spans nearly half that of Mercury’s orbit in the solar system.

Two monster black holes in the galaxy called NGC 7727 have been displayed in the animation. Situated roughly 1,600 light-years away, one weighs around 6 million solar masses and the other more than 150 million Suns. Astronomers state the fact that the pair will merge in the coming 250 million years.

Since 2015, gravitational wave observatories on Earth have detected the mergers of black holes with a few dozen solar masses thanks to the tiny ripples in space-time these events produce.

Ira Thorpe, Goddard Astrophysicist, National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Thorpe added, “Mergers of supermassive black holes will produce waves of much lower frequencies which can be detected using a space-based observatory millions of times larger than its Earth-based counterparts.”

This is the reason for NASA to come into partnership with the ESA (European Space Agency) to come up with their LISA mission, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, anticipated to launch sometime in the next 10 years.

A constellation of three spacecraft in a triangle has been comprised by LISA that shoots laser beams back and forth over millions of miles to accurately quantify their separations.

This will allow the detection of passing gravitational waves from combining black holes with masses reaching up to a few hundred million Suns. To handle even bigger mergers, astronomers are exploring other detection methods.

At the larger scale of the animation comes M87’s black hole, currently having an updated mass of nearly 5.4 billion Suns. Its shadow appears to be so big that even a beam of light—traveling at around 670 million mph (1 billion kph)—would take almost two and a half days to cross it.

The movie ends with TON 618, one of a handful of extremely farther and huge black holes for which astronomers consist of direct measurements. This behemoth contains over 60 billion solar masses, and it promotes a shadow so large that a beam of light would take around weeks to traverse it.

All monster black holes are not equal. Watch this video to see how they compare to each other and to our solar system. The black holes shown, which range from 100,000 to more than 60 billion times our Sun’s mass, are scaled according to the sizes of their shadows – a circular zone about twice the size of their event horizons. Only one of these colossal objects resides in our galaxy, and it lies 26,000 light-years away. Smaller black holes are shown in bluish colors because their gas is expected to be hotter than that orbiting larger ones. Scientists think all of these objects shine most intensely in ultraviolet light. Video Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab