Dec 3 2014

Physicist Tobias Kippenberg measures and manipulates oscillators that are tiny yet still visible to the naked eye. Their optical and mechanical properties are governed by the laws of quantum physics. In recognition of his innovative work he has been awarded the National Latsis Prize 2014.

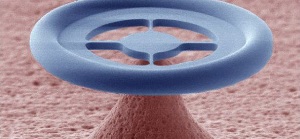

Electron microscopy image of the glass donut, which is smaller than the diameter of a hair. It is connected to the supporting chip by four spokes, to ensure that the structure can vibrate for a long time like a good tuning fork. Light can circulate up to a million times around the circumference of the donut. As the light bounces against the walls of the structure, it exerts a small force on the glass, which can influence the vibrations of the structure. © K-Lab/EPFL

Electron microscopy image of the glass donut, which is smaller than the diameter of a hair. It is connected to the supporting chip by four spokes, to ensure that the structure can vibrate for a long time like a good tuning fork. Light can circulate up to a million times around the circumference of the donut. As the light bounces against the walls of the structure, it exerts a small force on the glass, which can influence the vibrations of the structure. © K-Lab/EPFL

The laws of quantum physics apply in general at very small scales, governing the behaviour of elementary particles or atoms. Tobias Kippenberg, professor at the Laboratory of Photonics and Quantum Measurements at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, EPFL), is seeking to discover, observe and study these laws in macroscopic “mechanical resonators” that are formed from billions of atoms. The 38-year old physicist’s basic research in cavity quantum optomechanics has earned him the National Latsis Prize 2014.

Following his undergraduate degree at the Technical University of Aachen, which preceded a Master of Science, a PhD and post-doctorate research at Caltech in Pasadena, California, Tobias Kippenberg spent a number of years as an independent researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Germany, where he collaborated with physics Nobel laureate, Professor Theodor Hänsch. He joined EPFL in 2008 and was promoted to full professor in 2013.

Tiny structures

His current work focuses on miniature ring-shaped glass oscillators, with spokes like bicycle wheels, that are just 24 microns in diameter, corresponding to less than half the width of a human hair. Light is able to move around the circumference of the ring (as though within the tyre of the bicycle wheel), producing by means of internal reflection what the physicists term “radiation pressure.” The result is a slight mechanical vibration.

The resonators are designed to allow them to store photons (light) and phonons (vibrations) in a micro cavity for a relatively long period of time.

Almost absolute zero

In Tobias Kippenberg’s experiments, the device is first cooled to within half a degree of absolute zero (-273.15 °C). However, even this extreme cold is not sufficient to allow quantum behaviour to be observed, as the thermal excitation in the mechanical oscillator causes what is called “quantum decoherence.” In an article published in Nature in 2012, Kippenberg and his team showed for the first time that by further reducing the temperature of the mechanical oscillator by injecting laser light, they were able to reach the regime of “quantum coherent coupling” between light and a mechanical oscillator. During this process, the interaction between the light and vibrations of the resonator is so strong that its mechanical and optical properties cannot be separated. The exchange of the quantum states between the mechanical oscillator and the light field becomes in this regime faster than their decoherence.

At this point, the oscillator is so cold that it spends more than a third of its time in its quantum state. In this mode, it exhibits minimum vibration that can only be described by the laws of quantum mechanics (a theory that predicts in particular that an object can never be perfectly immobile, even when its temperature is at absolute zero).

Practical quantum physics

In parallel to his basic research on quantum optomechanics, Tobias Kippenberg also considers the applications of his work. In particular, he has discovered another remarkable property of microresonators: by connecting the light of a laser beam to a microresonator using an optical fibre it is possible to produce a so-called optical frequency comb.

Frequency combs are used in particular in the ultra high-precision calibration of astronomical spectrometers or to improve the accuracy of atomic clocks. The problem with current devices is that they are table-sized, extremely complex and have a very fine teeth spacing. Tobias Kippenberg’s devices, in contrast, are miniaturised, exhibit large comb teeth spacing and are constructed using the same techniques as those used to manufacture electronic chips. His first patent for this technology was registered in 2007, with a second following in 2013. The German researcher now hopes to take the next step towards the commercialisation of his invention, with a start-up company.

The National Latsis Prize, which is worth CHF 100,000, is among the most important scientific honours in Switzerland. The SNSF awards the prize on behalf of the International Latsis Foundation to young researchers up to the age of 40 for exceptional scientific work conducted in Switzerland.

The prize, which will be awarded for the thirty first time this year, will be presented in a ceremony at the town-hall in Berne, at 10.30 to 12.00 hours on 14 January 2015 in Berne. Attendance at the ceremony is open to members of the press and media.