Aug 2 2013

Our universe is filled with gobs of galaxies, bound together by gravity into larger families called clusters. Lying at the heart of most clusters is a monster galaxy thought to grow in size by merging with neighboring galaxies, a process astronomers call galactic cannibalism.

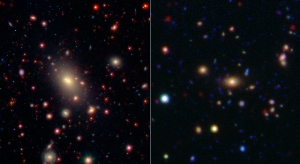

This image shows two of the galaxy clusters observed by NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and Spitzer Space Telescope missions. Galaxy clusters are among the most massive structures in the universe. The central and largest galaxy in each grouping, called the brightest cluster galaxy or BCG, is seen at the center of each image. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SDSS/NOAO

This image shows two of the galaxy clusters observed by NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and Spitzer Space Telescope missions. Galaxy clusters are among the most massive structures in the universe. The central and largest galaxy in each grouping, called the brightest cluster galaxy or BCG, is seen at the center of each image. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SDSS/NOAO

New research from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) is showing that, contrary to previous theories, these gargantuan galaxies appear to slow their growth over time, feeding less and less off neighboring galaxies.

"We've found that these massive galaxies may have started a diet in the last 5 billion years, and therefore have not gained much weight lately," said Yen-Ting Lin of the Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan, lead author of a study published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Peter Eisenhardt, a co-author from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said, "WISE and Spitzer are letting us see that there is a lot we do understand -- but also a lot we don't understand -- about the mass of the most massive galaxies." Eisenhardt identified the sample of galaxy clusters studied by Spitzer, and is the project scientist for WISE.

The new findings will help researchers understand how galaxy clusters -- among the most massive structures in our universe -- form and evolve.

Galaxy clusters are made up of thousands of galaxies, gathered around their biggest member, what astronomers call the brightest cluster galaxy, or BCG. BCGs can be up to dozens of times the mass of galaxies like our own Milky Way. They plump up in size by cannibalizing other galaxies, as well as assimilating stars that are funneled into the middle of a growing cluster.

To monitor how this process works, the astronomers surveyed nearly 300 galaxy clusters spanning 9 billion years of cosmic time. The farthest cluster dates back to a time when the universe was 4.3 billion years old, and the closest, when the universe was much older, 13 billion years old (our universe is presently 13.8 billion years old).

"You can't watch a galaxy grow, so we took a population census," said Lin. "Our new approach allows us to connect the average properties of clusters we observe in the relatively recent past with ones we observe further back in the history of the universe."

Spitzer and WISE are both infrared telescopes, but they have unique characteristics that complement each other in studies like these. For instance, Spitzer can see more detail than WISE, which enables it to capture the farthest clusters best. On the other hand, WISE, an infrared all-sky survey, is better at capturing images of nearby clusters, thanks to its larger field of view. Spitzer is still up and observing; WISE went into hibernation in 2011 after successfully scanning the sky twice.

The findings showed that BCG growth proceeded along rates predicted by theories until 5 billion years ago, or a time when the universe was about 8 billion years old. After that time, it appears the galaxies, for the most part, stopped munching on other galaxies around them.

The scientists are uncertain about the cause of BCGs' diminished appetites, but the results suggest current models need tinkering.

"BCGs are a bit like blue whales -- both are gigantic and very rare in number. Our census of the population of BCGs is in a way similar to measuring how the whales gain their weight as they age. In our case, the whales aren't gaining as much weight as we thought. Our theories aren't matching what we observed, leading us to new questions," said Lin.

Another possible explanation is that the surveys are missing large numbers of stars in the more mature clusters. Clusters can be violent environments, where stars are stripped from colliding galaxies and flung into space. If the recent observations are not detecting those stars, it's possible that the enormous galaxies are, in fact, continuing to bulk up.

Future studies from Lin and others should reveal more about the feeding habits of one of nature's largest galactic species.