Jul 24 2013

Purple bacteria contain pigments that allow them to use sunlight as their source of energy, hence their color. Small as they are, these microbes can teach us a lot about life on Earth, because they have been around longer than most other organisms on the planet.

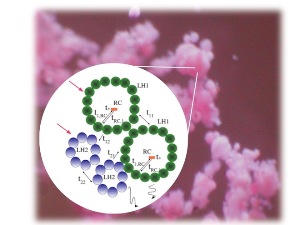

Purple bacteria make a "gel" around the individual cells which binds them into a colony. That is why they appear as "clouds." The insert illustrates the general principle of the model used in the study. It depicts photons arriving, then being passed around the bacteria’s membrane, where the light ha

Purple bacteria make a "gel" around the individual cells which binds them into a colony. That is why they appear as "clouds." The insert illustrates the general principle of the model used in the study. It depicts photons arriving, then being passed around the bacteria’s membrane, where the light ha

University of Miami (UM) physicist Neil Johnson, who studies purple bacteria, recently found that these organisms can also survive in the presence of extreme alien light. The findings show that the way in which light is received by the bacteria can dictate the difference between life and death.

Johnson, head of the inter-disciplinary research group in complexity in the College of Arts and Sciences at UM and his collaborators share their findings in a paper titled “Extreme alien light allows survival of terrestrial bacteria” published online in Nature's Scientific Reports. The study reveals new possibilities for life on earth and elsewhere in the universe.

“The novelty of our work is that despite all the effort aimed at finding planets outside our solar system where life might exist, people have ignored the fact that photosynthesis--and hence life on Earth-- isn't just about having the right atmosphere and light intensity,” Johnson says. “Instead, as we show, a crucial missing ingredient is how the light arrives at the organism.”

The results are also applicable in the scenario of our own sun developing extreme fluctuations and in a situation in which bacteria are subject to extreme artificial light sources in the laboratory. The findings may also help with engineering a new generation of designer-light-harvesting structures.

Using a mathematical model the researchers calculated the probability of survival when the bacteria is subjected to bursts of light, similar to what might be experienced if the light source was an unstable star. The flow of light was on average the same as the bacteria would normally receive, but since they would be receiving it in such a strange way, the researchers wondered under what situations the bacteria could survive.

“It’s like saying we know we need to bring home a certain amount of food per week, but what happens if all of the food is delivered in one day? You might not be able to store all of it,” Johnson says. “Maybe some food would get spoiled, or maybe you wouldn't have time to use it all,” he says. “The light is like food for the bacteria, and the issue is the amount of food and the timing with which you bring it in.”

Light comes in packets of photons. Purple bacteria process light in places called reaction centers, where the energy of the photons fuels the production of metabolic materials. Johnson compares the situation to asking what happens when food arrives in the kitchen in an irregular way.

“The reaction center, like any kitchen, can’t do a thousand things at once. They can only handle one photon at a time,” Johnson says. “The new chemicals made in the process take some time to diffuse. Otherwise, it results in a buildup of chemicals that can kill the bacteria,” he says. “Since we are concluding this from statistical calculations, we can say it’s very unlikely that the bacteria will survive.”

To their surprise, the researchers found that while many seemingly innocuous changes in the way the light arrives at the organisms end up proving fatal, the bacteria could survive a sudden deluge of photons. The key to enduring such extreme conditions is that that there are many reaction center ‘kitchens.’ Therefore, the photons spread out naturally, leaving each reaction center enough time to recover.

“Ultimately the chemicals have time to diffuse and that is what saves it,” Johnson says. “On the average the bacteria is therefore getting what it needs from the reaction centers.”

The researchers suspect this mechanism is not unique to purple bacteria. In the future, they will expand the study to other photosynthetic life forms. Co-authors of the study are Guannan Zhao, who was a postdoctoral fellow at UM at the time of the project; Pedro Manrique and Hong Qi doctoral students at UM; Felipe Caycedo, postdoctoral fellow at Universitat Ulm, Germany; Ferney Rodriguez and Luis Quiroga, professors at Universidad de Los Andes, Bogota, Colombia.

CREDIT: Dr.Wayne B. Lanier