Astronomers worldwide are fascinated by a remarkably bright and continuous pulse of high-energy radiation that drifted across the Earth on October 9th, 2022. The emission was discharged by a gamma-ray burst (GRB)—the most dominant category of explosions in the universe—that falls among the group of most luminous events ever witnessed.

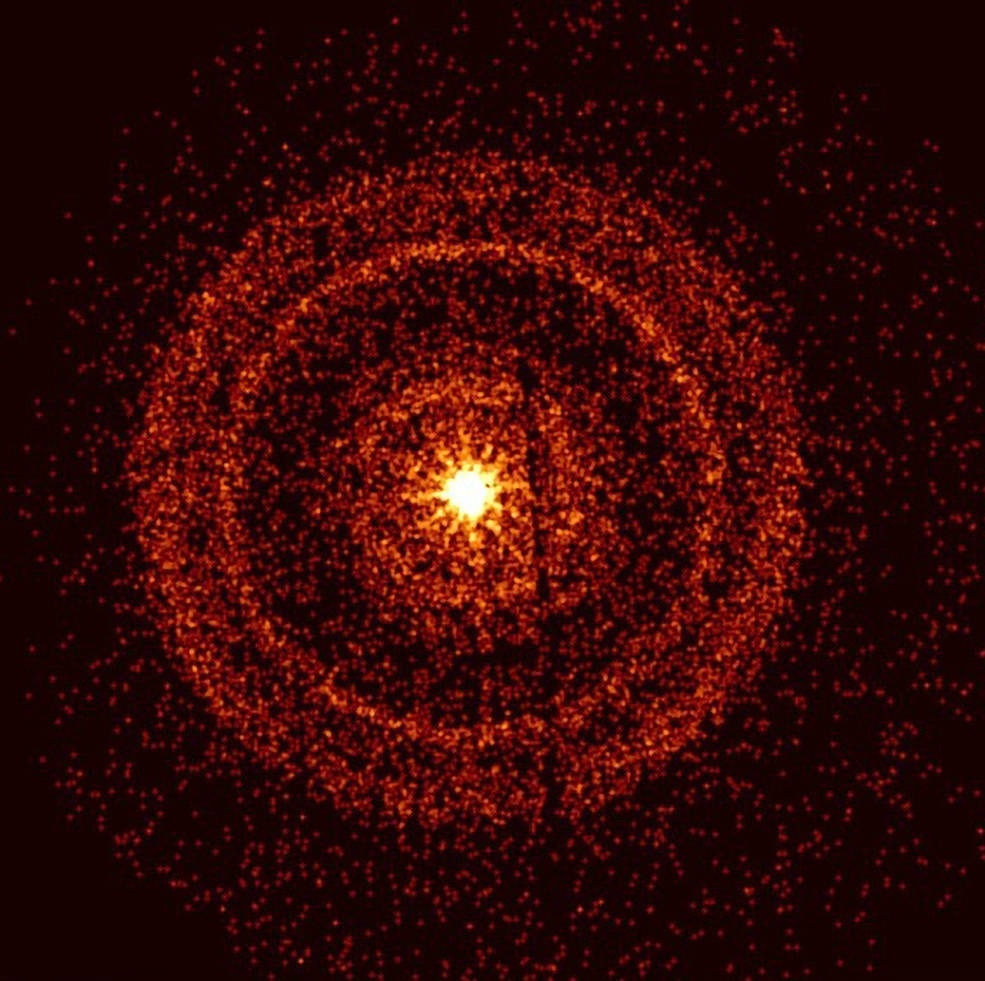

Swift’s X-Ray Telescope captured the afterglow of GRB 221009A about an hour after it was first detected. The bright rings form as a result of X-rays scattered from otherwise unobservable dust layers within our galaxy that lie in the direction of the burst. Image Credit: NASA/Swift/A. Beardmore (University of Leicester).

On the morning of October 9th (Eastern time), 2022, a wave of X-rays and gamma rays swept through the solar system, activating detectors aboard NASA's Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope, Wind spacecraft, and Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, as well as others. Globally, telescopes shifted toward the site to investigate the aftermath, and new observations are ongoing.

Referred to as GRB 221009A, the explosion has offered a surprisingly sensational start to the 10th Fermi Symposium happening in Johannesburg, South Africa, in which gamma-ray astronomers from around the world are participating.

It’s safe to say this meeting really kicked off with a bang—everyone’s talking about this.

Judy Racusin, Fermi Deputy Project Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center, National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Fermi Deputy Project Scientist Judy Racusin is attending the conference.

The signal, stemming from the direction of the constellation Sagitta, had covered approximately 1.9 billion years to reach Earth. Astronomers believe it signifies the birth cry of a new black hole, one that developed in the center of an enormous star disintegrating under its own weight.

In these conditions, a budding black hole drives strong jets of particles moving almost at the speed of light. The jets penetrate through the star, releasing gamma rays and X-rays as they travel into space.

The burst also offered a much-awaited initial observing opportunity for a connection between two experiments on the International Space Station—NASA’s NICER X-ray telescope and a Japanese detector known as the Monitor of All-sky X-ray Image (MAXI).

Initiated in April, the connection is labeled the Orbiting High-energy Monitor Alert Network (OHMAN). It enables NICER to quickly turn to outbursts identified by MAXI, actions that formerly needed intervention by experts on the ground.

OHMAN provided an automated alert that enabled NICER to follow up within three hours, as soon as the source became visible to the telescope. Future opportunities could result in response times of a few minutes.

Zaven Arzoumanian, Science Lead, NICER, Goddard Space Flight Center, National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The light from this prehistoric explosion offers new insights into the birth of a black hole, the astronomical collapse, the behavior and interaction of matter close to the speed of light, the conditions in a faraway galaxy—and much more. There may not be another GRB this bright for decades.

According to a primary investigation, Fermi’s Large Area Telescope (LAT) identified the burst for over 10 hours. One possibility for the burst’s longevity and brightness is that, for a GRB, it lies comparatively close to us.

This burst is much closer than typical GRBs, which is exciting because it allows us to detect many details that otherwise would be too faint to see. But it’s also among the most energetic and luminous bursts ever seen regardless of distance, making it doubly exciting.

Roberta Pillera, Fermi LAT Collaboration Member and Doctoral Student, Polytechnic University of Bari

Roberta Pillera led the preliminary communications about the burst.