A research group headed by Lund University in Sweden has given a vital clue to the origin of the element Ytterbium present in the Milky Way, by revealing that the element mainly originates from supernova explosions.

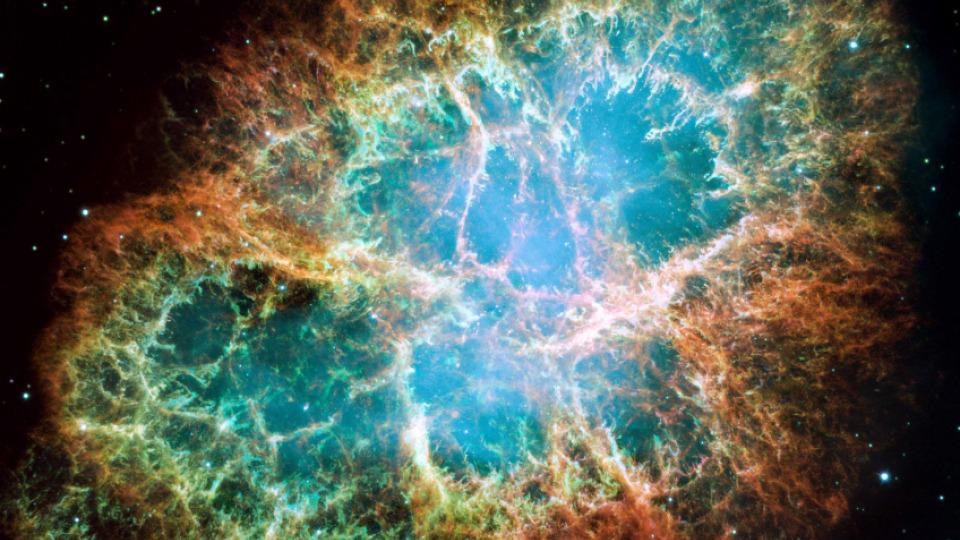

The Crab Nebula. Image Credit: NASA/ESA/J Hester Arizona State University.

The Crab Nebula. Image Credit: NASA/ESA/J Hester Arizona State University.

The pioneering research also offers fresh opportunities for learning about the evolution of the galaxy. The research is published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Named after the Ytterby mine in the Stockholm archipelago, Ytterbium is one of four elements in the periodic table. The element was first found in the black mineral gadolinite — first identified in 1787 in the Ytterby mine.

Ytterbium is interesting as it could have two diverse cosmic origins. Scientists believe that one-half originates from heavy stars having short lives. Whereas the other half originates from more regular stars, a lot like the sun, and they produce Ytterbium in the last stages of their comparatively long lives.

By studying stars formed at different times in the Milky Way, we have been able to investigate how fast the Ytterbium content increased in the galaxy. What we have succeeded in doing is adding relatively young stars to the study.

Martin Montelius, University of Groningen

Martin Montelius was an astronomy researcher at Lund University during the time of the research.

It has been assumed that Ytterbium was flung into space by stellar winds, supernova explosions and planetary nebulae. It gathered in large space clouds there, from which new stars were created.

By analyzing high-quality spectra of nearly 30 stars in the sun’s proximity, the scientists were capable of providing significant experimental backing for the theory of the cosmic origin of Ytterbium. Ytterbium appears to majorly originate from supernova explosions.

The instrument we used is a super-sensitive spectrometer that can detect infrared light in high resolution. It was used with two telescopes in the southern United States, one in Arizona and one in Texas.

Martin Montelius, University of Groningen

As the examination of Ytterbium was performed using infrared light, it is now possible to analyze large areas of the Milky Way that exist behind impenetrable dust. As the red light from a sunset passes through the Earth’s atmosphere, infrared light can pass through the dust in a similar way.

Our study opens up the possibility of mapping extensive parts of the Milky Way that have previously been unexplored. This means that we will be able to compare the evolutionary history in different parts of the galaxy.

Rebecca Forsberg, Doctoral Student, Astronomy, Lund University

The research group employed the IGRINS instrument for their calculations, designed at the University of Texas at Austin and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

Journal Reference:

Montelius, M., et al. (2022) Chemical Evolution of Ytterbium in the Galactic Disk. Astronomy & Astrophysics. doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2202.00691.