May 13 2013

The stars, known as white dwarfs — small, dim remnants of stars once like the Sun — reside 150 light-years away in the Hyades star cluster, in the constellation of Taurus (The Bull). The cluster is relatively young, at only 625 million years old.

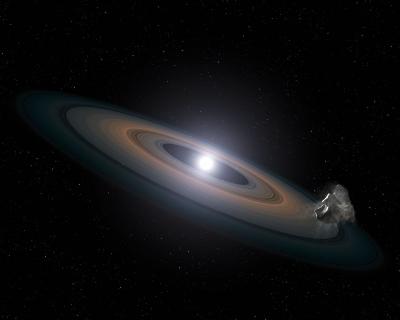

This illustration is an artist's impression of the thin, rocky debris disc discovered around the two Hyades white dwarfs. Rocky asteroids are thought to have been perturbed by planets within the system and diverted inwards towards the star, where they broke up, circled into a debris ring, and were then dragged onto the star itself. Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, and G. Bacon (STScI)

This illustration is an artist's impression of the thin, rocky debris disc discovered around the two Hyades white dwarfs. Rocky asteroids are thought to have been perturbed by planets within the system and diverted inwards towards the star, where they broke up, circled into a debris ring, and were then dragged onto the star itself. Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, and G. Bacon (STScI)

Astronomers believe that all stars formed in clusters. However, searches for planets in these clusters have not been fruitful — of the roughly 800 exoplanets known, only four are known to orbit stars in clusters. This scarcity may be due to the nature of the cluster stars, which are young and active, producing stellar flares and other outbursts that make it difficult to study them in detail.

A new study led by Jay Farihi of the University of Cambridge, UK, instead observed "retired" cluster stars to hunt for signs of planet formation.

Hubble's spectroscopic observations identified silicon in the atmospheres of two white dwarfs, a major ingredient of the rocky material that forms Earth and other terrestrial planets in the Solar System. This silicon may have come from asteroids that were shredded by the white dwarfs' gravity when they veered too close to the stars. The rocky debris likely formed a ring around the dead stars, which then funnelled the material inwards.

The debris detected whirling around the white dwarfs suggests that terrestrial planets formed when these stars were born. After the stars collapsed to form white dwarfs, surviving gas giant planets may have gravitationally nudged members of any leftover asteroid belts into star-grazing orbits.

"We have identified chemical evidence for the building blocks of rocky planets," says Farihi. "When these stars were born, they built planets, and there's a good chance that they currently retain some of them. The signs of rocky debris we are seeing are evidence of this — it is at least as rocky as the most primitive terrestrial bodies in our Solar System."

Besides finding silicon in the Hyades stars' atmospheres, Hubble also detected low levels of carbon. This is another sign of the rocky nature of the debris, as astronomers know that carbon levels should be very low in rocky, Earth-like material. Finding its faint chemical signature required Hubble's powerful Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS), as carbon's fingerprints can be detected only in ultraviolet light, which cannot be observed from ground-based telescopes.

"The one thing the white dwarf pollution technique gives us that we won't get with any other planet detection technique is the chemistry of solid planets," Farihi says. "Based on the silicon-to-carbon ratio in our study, for example, we can actually say that this material is basically Earth-like."

This new study suggests that asteroids less than 160 kilometres across were gravitationally torn apart by the white dwarfs' strong tidal forces, before eventually falling onto the dead stars.

The team plans to analyse more white dwarfs using the same technique to identify not only the rocks' composition, but also their parent bodies. "The beauty of this technique is that whatever the Universe is doing, we'll be able to measure it," Farihi said. "We have been using the Solar System as a kind of map, but we don't know what the rest of the Universe does. Hopefully with Hubble and its powerful ultraviolet-light spectrograph COS, and with the upcoming ground-based 30- and 40-metre telescopes, we'll be able to tell more of the story."