Mar 16 2020

Physicists at RIKEN have performed calculations and unraveled the behavior of electrons in a nickel oxide material, which could be helpful in the search for high-temperature superconductors.

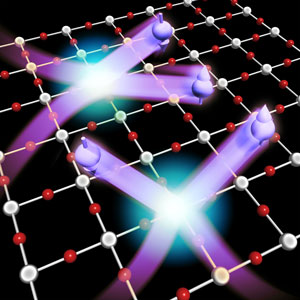

Electrons (lilac) interact strongly with one another as they move through the NiO2 layer of a nickelate material, which could act as a model for high-temperature superconductivity (nickel = gray, oxygen = red). Image Credit: Image produced by Mari Ishida of the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science. © 2020 RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science.

Electrons (lilac) interact strongly with one another as they move through the NiO2 layer of a nickelate material, which could act as a model for high-temperature superconductivity (nickel = gray, oxygen = red). Image Credit: Image produced by Mari Ishida of the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science. © 2020 RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science.

Superconductors have the ability to transport electrical current without any resistance. They are used to develop powerful electromagnets or sensitive instruments to measure magnetic fields.

Traditional superconductivity is based on a kind of electron pairing that takes place only at very low temperatures. Therefore, it is essential to cool down superconducting devices using high-cost liquefied gases.

However, nearly three decades earlier, scientists found that certain cuprate materials exhibited the potential to turn into superconductors at comparatively warm temperatures, of up to −140 °C. The fundamental cause of this high-temperature superconductivity is still not clear.

In 2019, scientists discovered that a strontium-doped neodymium nickel oxide (Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2) had the ability to superconduct below the temperature of −258 °C. The finding became famous not due to the temperature but because the crystal structure of the nickelate material is quite similar to that of cuprates, and may be useful as a test-bed to gain better insights into how superconductivity works in such materials.

The nickelate material includes alternating layers of NiO2 and Nd. Yusuke Nomura and his team from the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science investigated the impact of the interactions between specific electrons in these two layers on superconductivity.

The calculations performed by the researchers revealed that the electrons in the NiO2 layer interact strongly with one another. This phenomenon is analogous to cuprates in which the strong correlation in the CuO2 layer is regarded to have a major role in their high-temperature superconductivity.

But the cuprates and nickelates are different in one way: electrons in the neodymium layer of the nickelates are partially occupied, thereby forming the Fermi pocket—a comparatively small region in the Brillouin zone around which the Fermi surface exists. Such pockets do not exist in cuprates, which may render the nickelate material an imperfect match for cuprates.

Computational models were used by Nomura and his colleagues to analyze whether the pockets could be avoided by adjusting the material’s chemical composition, thereby creating a nickelate that is a better analog for the cuprates.

The researchers discovered that two compounds could be a better fit: sodium calcium nickel oxide (NaCa2NiO3) and sodium neodymium nickel oxide (NaNd2NiO4).

If the proposed nickelates are synthesized, they will be real nickel analogues of cuprate superconductors. The next stage is to clarify the difference and similarity between the nickelates and cuprates in a more systematic way, and get deeper insight into the superconducting mechanism in both systems.

Yusuke Nomura, Researcher, RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science