Jan 8 2020

Wolf Cukier’s job as a summer intern at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, in 2019 was to investigate variations in star brightness that NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) captures and uploads to the Planet Hunters TESS citizen science project.

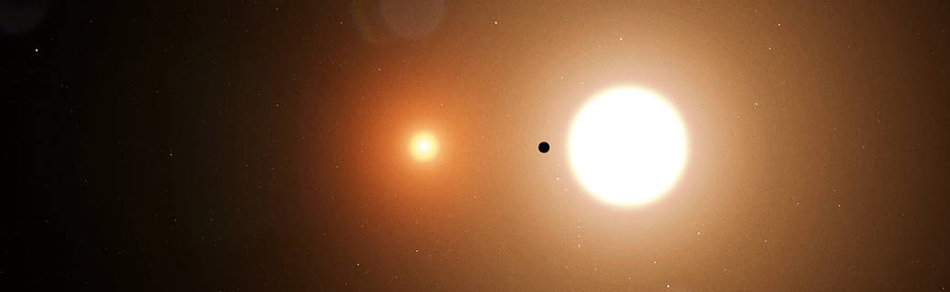

TOI 1338 b is silhouetted by its host stars. TESS only detects transits from the larger star. Image Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Chris Smith.

TOI 1338 b is silhouetted by its host stars. TESS only detects transits from the larger star. Image Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Chris Smith.

Cukier joined Goddard Space Flight Center after completing his junior year in 2019 at Scarsdale High School in New York.

I was looking through the data for everything the volunteers had flagged as an eclipsing binary, a system where two stars circle around each other and from our view eclipse each other every orbit. About three days into my internship, I saw a signal from a system called TOI 1338. At first I thought it was a stellar eclipse, but the timing was wrong. It turned out to be a planet.

Wolf Cukier, Researcher, Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA

TESS’s first circumbinary planet, which is currently known as TOI 1338 b, is a world that orbits two stars. The finding was reported in a panel discussion held at the 235th American Astronomical Society meeting in Honolulu, on Monday, January 6th, 2020.

A paper, co-authored by Cukier along with researchers from Goddard, San Diego State University, the University of Chicago, and other institutions, has been submitted for publication to a scientific journal.

The TOI 1338 system is located 1,300 light-years away in the Pictor constellation. One of the two stars orbiting each other, every fortnight, is nearly 10% larger than the Sun. The other star is dimmer, cooler, and just one-third the mass of the Sun.

TOI 1338 b is the only familiar planet in the system is nearly 6.9 times larger compared to Earth. Its size is between that of Neptune and Saturn. Since the planet orbits in almost precisely the same plane as the stars, it undergoes regular stellar eclipses.

TESS is equipped with four cameras, each capturing a full-frame image of a sky patch every 30 minutes continuously for 27 days. Using the observations, the researchers create graphs of the change in the brightness of stars over time. If a planet crosses in front of its star from Earth’s perspective—an event called a transit—its passage leads to a unique dip in the brightness of the star.

However, it is highly challenging to detect planets that orbit two stars compared to those that orbit one. The transits of the TOI 1338 b are irregular, between every 93 and 95 days, and differ in duration and depth due to the orbital motion of its stars. TESS observes only the transits of the larger star; the transits of the smaller star cannot be detected as they are too faint.

These are the types of signals that algorithms really struggle with. The human eye is extremely good at finding patterns in data, especially non-periodic patterns like those we see in transits from these systems.

Veselin Kostov, Study Lead Author, Research Scientist, SETI Institute and Goddard Space Flight Center

This points out why Cukier had to perform a visual inspection of each potential transit. For instance, he first considered the transit of TOI 1338 b was due to the passage of the smaller star in the system in front of the larger one—both lead to analogous dips in brightness. However, the timing was wrong for an eclipse.

Once TOI 1338 b was identified, the researchers employed a software package known as Eleanor, taking its name from Eleanor Arroway, the central character in Carl Sagan’s novel “Contact,” to verify that the transits were real and not caused by instrumental artifacts.

Throughout all of its images, TESS is monitoring millions of stars. That’s why our team created eleanor. It’s an accessible way to download, analyze and visualize transit data. We designed it with planets in mind, but other members of the community use it to study stars, asteroids and even galaxies.

Adina Feinstein, Study Co-Author, Graduate Student, University of Chicago

Using radial velocity surveys, TOI 1338 was already investigated from the ground. The surveys involve measuring motion along the line of sight of researchers. This archival data was used by Kostov’s team to investigate the system and verify the planet.

The orbit of the planet will remain stable for a minimum of 10 million years. However, the angle of the orbit with respect to Earth changes such that the planet transit will stop after November 2023 and resume again eight years later.

Previously, the K2 and Kepler missions from NASA identified 12 circumbinary planets in 10 systems, all analogous to TOI 1338 b. According to Kostov, observations of binary systems are biased toward discovering larger planets.

When smaller bodies transit, not much effect on the brightness of the stars occurs. It is anticipated that TESS will observe several hundred thousands of eclipsing binaries as part of its preliminary two-year mission, hence several of these circumbinary planets could be discovered.

TESS is a NASA Astrophysics Explorer mission headed and operated by MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Northrop Grumman, based in Falls Church, Virginia; NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley; the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts; MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory; and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore are the additional partners. More than a dozen research institutes, universities, and observatories across the world participated in the mission.

TESS Satellite Discovered Its 1st World Orbiting 2 Stars

Researchers working with data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) have discovered the mission’s first circumbinary planet, a world orbiting two stars. The planet, called TOI 1338 b, is around 6.9 times larger than Earth, or between the sizes of Neptune and Saturn. It lies in a system 1,300 light-years away in the constellation Pictor. The stars in the system make an eclipsing binary, which occurs when the stellar companions circle each other in our plane of view. One is about 10% more massive than our Sun, while the other is cooler, dimmer and only one-third the Sun’s mass. TOI 1338 b’s transits are irregular, between every 93 and 95 days, and vary in depth and duration thanks to the orbital motion of its stars. TESS only sees the transits crossing the larger star—the transits of the smaller star are too faint to detect. Its orbit is stable for at least the next 10 million years. The orbit’s angle to us, however, changes enough that the planet transit will cease after November 2023 and resume eight years later. Video Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.