Apr 24 2013

Astronomers have found a galaxy turning gas into stars with almost 100 percent efficiency, a rare phase of galaxy evolution that is the most extreme yet observed. The findings come from the IRAM Plateau de Bure interferometer in the French Alps, NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer and NASA's Hubble Space Telescope.

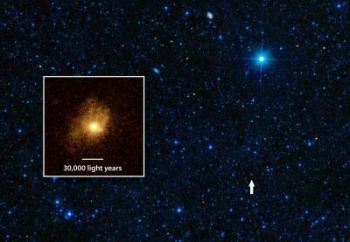

The tiny red spot in this image is one of the most efficient star-making galaxies ever observed, converting gas into stars at the maximum possible rate. The galaxy is shown here in an image from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), which first spotted the rare galaxy in infrared light. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/STScI/IRAM

The tiny red spot in this image is one of the most efficient star-making galaxies ever observed, converting gas into stars at the maximum possible rate. The galaxy is shown here in an image from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), which first spotted the rare galaxy in infrared light. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/STScI/IRAM

"Galaxies burn gas like a car engine burns fuel. Most galaxies have fairly inefficient engines, meaning they form stars from their stellar fuel tanks far below the maximum theoretical rate," said Jim Geach of McGill University, lead author of a new study appearing in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"This galaxy is like a highly tuned sports car, converting gas to stars at the most efficient rate thought to be possible," he said.

The galaxy, called SDSSJ1506+54, jumped out at the researchers when they looked at it using data from WISE's all-sky infrared survey. Infrared light is pouring out of the galaxy, equivalent to more than a thousand billion times the energy of our sun.

"Because WISE scanned the entire sky, it detected rare galaxies like this one that stand out from the rest," said Ned Wright of UCLA, the WISE principal investigator.

Hubble's visible-light observations revealed that the galaxy is extremely compact, with most of its light emanating from a region just a few hundred light-years across.

"This galaxy is forming stars at a rate hundreds of times faster than our Milky Way galaxy, but the sharp vision of Hubble revealed that the majority of the galaxy's starlight is being emitted by a region just a few percent of the diameter of the Milky Way. This is star formation at its most extreme," said Geach.

The team then used the IRAM Plateau de Bure Interferometer to measure the amount of gas in the galaxy. The ground-based telescope detected millimeter-wave light coming from carbon monoxide, an indicator of the presence of hydrogen gas, which is fuel for stars. Combining the rate of star formation derived with WISE, and the gas mass measured by IRAM, the scientists get a measure of the star formation efficiency.

The results reveal that the star-forming efficiency of the galaxy is close to the theoretical maximum, called the Eddington limit. In regions of galaxies where new stars are forming, parts of gas clouds are collapsing due to gravity. When the gas is dense enough to squeeze atoms together and ignite nuclear fusion, a star is born. At the same time, winds and radiation from stars that have just formed can prevent the formation of new stars by exerting pressure on the surrounding gas, curtailing the collapse.

The Eddington limit is the point at which the force of gravity pulling gas together is balanced by the outward pressure from the stars. Above the Eddington limit, the gas clouds would be blown apart, halting star formation.

"We see some gas outflowing from this galaxy at millions of miles per hour, and this gas may have been blown away by the powerful radiation from the newly formed stars," said Ryan Hickox, an astrophysicist at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., and a co-author on the study.

Why is SDSSJ1506+54 so unusual? Astronomers say they're catching the galaxy in a short-lived phase of evolution, possibly triggered by the merging of two galaxies into one. The star-formation is so ferocious that in a few tens of millions of years, the blink of an eye in a galaxy's life, the gas will be used up, and the galaxy will mature into a massive elliptical galaxy.

The scientists also used data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the W.M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii and the MMT Observatory on Mount Hopkins, Arizona.