Feb 27 2019

A team of Australian engineers and scientists has designed the local infrastructure for the world’s largest radio telescope – the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) – taking the billion-dollar global project one step closer to reality.

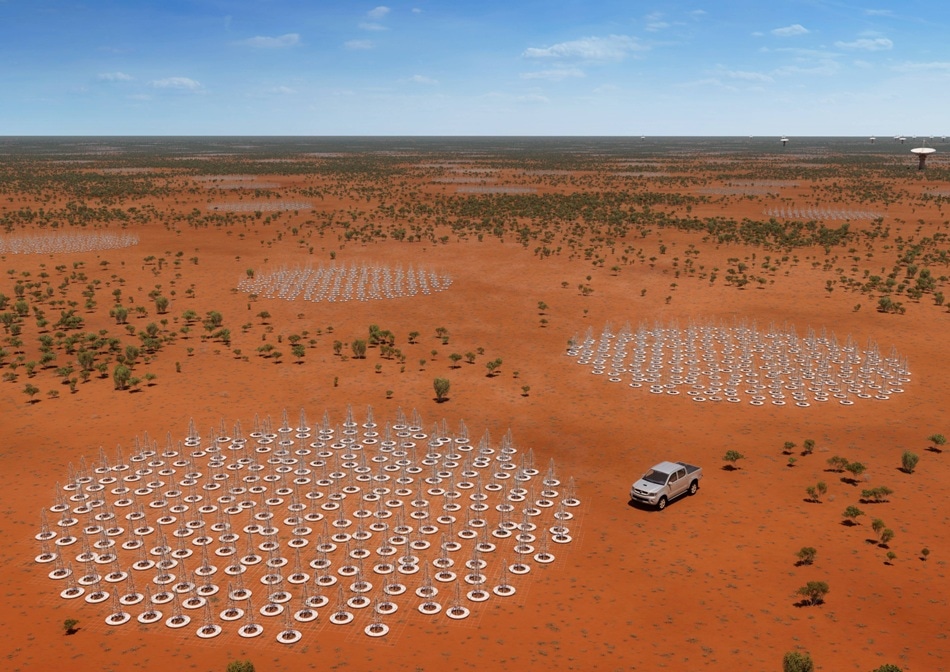

An artist’s impression of the future Square Kilometre Array (SKA) in Australia. Credit: SKA Organisation.

An artist’s impression of the future Square Kilometre Array (SKA) in Australia. Credit: SKA Organisation.

The SKA will explore the Universe in unprecedented detail, doing so hundreds of times faster than any current facility.

Antennas will be located in both Australia and southern Africa.

The SKA Infrastructure Australia consortium, led by CSIRO – Australia’s national science agency – and industry partner Aurecon Australia, has designed everything from supercomputing facilities, buildings, site monitoring and roads, to the power and data fibre distribution that will be needed to host the instrument at CSIRO’s Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in remote Western Australia.

The project has presented unique technical challenges.

“We’re setting the groundwork to host 132,000 low-frequency SKA antennas in Australia. These will receive staggering amounts of data,” CSIRO’s SKA Infrastructure Consortium Director, Antony Schinckel said.

“The data flows will be on the scale of petabits, or a million billion bits, per second – more than the global internet rate today, all flowing into a single building in the Murchison.

“To get this data from the antennas to the telescope’s custom supercomputing facilities we need to lay 65,000 fibre optic cables.”

CSIRO and Aurecon engineers drew on their experience working together on the infrastructure design for the Australian SKA Pathfinder telescope, CSIRO’s 36-dish radio telescope that is already operating at the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory.

Aurecon’s Senior Project Engineer, Shandip Abeywickrema, said the design team’s biggest challenge was minimising radio ‘noise’ created by the systems placed at the high-tech astronomy observatory.

This is essential to avoid drowning out the faint signals from space that the telescope is designed to detect.

“Containing the interference created by our own computing and power systems is an unusual construction requirement,” Mr Abeywickrema said.

“We’re trying to reduce the level of radio emissions by factors of billions.

“For example, the custom supercomputing building is effectively a fully welded box within a box, with the computing equipment to be located within the inner shield, while support plant equipment will be located in the outer shield.”

Australian SKA Director, David Luchetti said that while the CSIRO-Aurecon team has been working on the infrastructure designs for Australia, a second consortium had designed the infrastructure for the South African SKA site.

“CSIRO and Aurecon have delivered world-class designs, and the collaboration between the Australian and South African infrastructure consortia is a great example of the massive global effort behind the SKA project,” Mr Luchetti said.

“Infrastructure isn’t usually seen as an arena for innovation, but this project has produced innovative designs, in Australia, which may have applications beyond astronomy.

“In addition to the incredible scientific potential of this project, we expect that the SKA will generate many spin-off benefits that we can’t yet anticipate.

“We want to make sure Australia is best placed to capture these benefits.”

This design work was funded by the Australian Government and the European Union.

The Infrastructure Australia group, and counterparts designing SKA infrastructure in co-host country South Africa, are among 12 international engineering consortia each designing specific elements of the SKA.

These consortia represent 500 engineers and scientists in 20 countries.

Once all the design packages are complete and approved, a critical design review for the entire SKA system will take place ahead of a construction proposal being developed.

Construction is expected to begin in 2020.