Apr 11 2013

Topological insulators (TIs) are an exciting new type of material that on their surface carry electric current, but within their bulk, act as insulators. Since the discovery of TIs about a decade ago, their unique characteristics (which point to potential applications in quantum computing) have been explored theoretically, and in the last five years, experimentally.

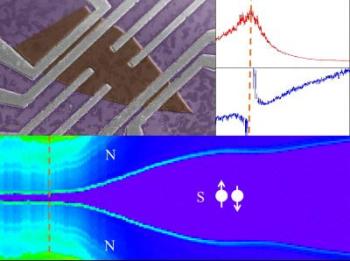

Top: This is an SEM image of a typical device. Mechanically exfoliated Bi2Se3 thin film is colored as brown and contact metals consist of Ti(2.5nm)/Al(140nm). Top right: Hall data where red curve is longitudinal resistivity and blue curve is Hall carrier density as a function of gate voltage. Credit: Sungjae Cho, Department of Physics & Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Top: This is an SEM image of a typical device. Mechanically exfoliated Bi2Se3 thin film is colored as brown and contact metals consist of Ti(2.5nm)/Al(140nm). Top right: Hall data where red curve is longitudinal resistivity and blue curve is Hall carrier density as a function of gate voltage. Credit: Sungjae Cho, Department of Physics & Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

But where in theory, the bulk of TIs carry no current, in the laboratory, impurities and disorder in real materials means the bulk is, in fact, conductive. This has proven an obstacle to experimentation with TIs: findings from prior experiments designed to test the surface conductivity of TIs unavoidably included contributions from the surplus of electrons in the bulk.

Now an interdisciplinary research team at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in collaboration with researchers at Brookhaven National Laboratory's Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science Department, has measured superconductive surface states in TIs where the bulk charge carriers were successfully depleted. The research paper, "Symmetry protected Josephson supercurrents in three-dimensional topological insulators," was published this week in Nature Communications.

The experiments, conducted in the laboratory of Illinois condensed matter physicist Nadya Mason at the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory, were carried out by postdoctoral research associate Sungjae Cho using TI material—specially developed by the Brookhaven team—coupled to superconducting leads.

To deplete the electrons in the bulk, the team used three strategies: the TI material was doped with antimony, then it was doped at the surface with a chemical with strong electron affinity, and finally an electrostatic gate was used to apply voltage that lowered the energy of the entire system.

"One of the main results we found," said Mason, "was in comparing the two experimental regimes, pure surface (bulk depleted of electrons) vs. bulk (excess electrons present in impurities in bulk material). We learned that even when you have the bulk, the superconductivity always goes through the surface of the material."

This finding was established by comparing experiments with theoretical modeling by research team members at Illinois's Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering—Asst. Professor Matthew Gilbert and graduate student Brian Dellabetta—which showed that superconductivity occured only at the surface of topological insulators and that this is a unique characteristic of these new materials.

It's been predicted that TIs harbor the highly sought Majorana quasiparticle, a fermion which is theorized to be its own antiparticle and which if discovered, could serve as a quantum bit in quantum computing.

"Since we now have a better understanding of how topological insulators behave with regard to superconductivity, this will assist our search for the Majorana quasiparticle," Mason explained.

The team also plans to investigate the same experimental configuration at lower energy to further explore its characteristics.

"The potential of this new material is very exciting. We are exploring possible uses for TIs in terms of conventional electronic devices and novel devices," said Mason. "And if we can find the new particle predicted to exist in the material's solid state, and then learn to manipulate its position relative to a second particle, we could use it for quantum computation.

"The implications for quantum computing are truly profound," she explained. "With today's technology, computer components really can't get much smaller. If Majoranas behave as predicted and can be manipulated to serve as quantum bits, our future computers would be extraordinarily powerful; their components would be much smaller and would be able to store much more information."