May 3 2018

Astronomers detect helium in the atmosphere of the exoplanet WASP-107b using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. This would be the first time helium has been detected in the atmosphere of a planet beyond the Solar System. The discovery proves the ability to apply infrared spectra to explore exoplanet extended atmospheres.

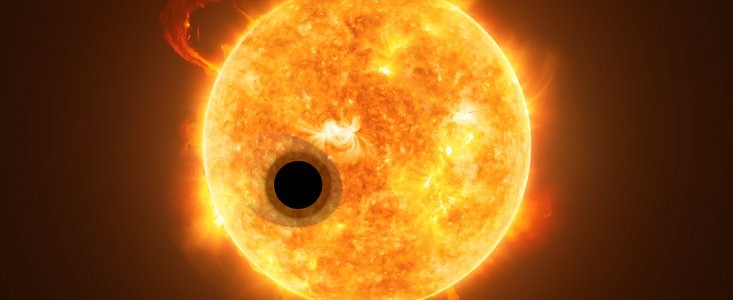

Artist’s impression of WASP-107b (Image credit: NASA, ESA)

Artist’s impression of WASP-107b (Image credit: NASA, ESA)

The international team of astronomers, guided by Jessica Spake, a Ph.D. student at the University of Exeter in the UK, used Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 to detect helium in the atmosphere of the exoplanet WASP-107b.

Spake states the significance of the discovery: “Helium is the second-most common element in the Universe after hydrogen. It is also one of the main constituents of the planets Jupiter and Saturn in our Solar System. However, up until now, helium had not been detected on exoplanets - despite searches for it.”

The team made the discovery by examining the infrared spectrum of the atmosphere of WASP-107b [1]. Earlier detections of extended exoplanet atmospheres have been made by examining the spectrum at optical and ultraviolet wavelengths; this detection thus shows that exoplanet atmospheres can also be explored at longer wavelengths.

The strong signal from helium we measured demonstrates a new technique to study upper layers of exoplanet atmospheres in a wider range of planets. Current methods, which use ultraviolet light, are limited to the closest exoplanets. We know there is helium in the Earth’s upper atmosphere and this new technique may help us to detect atmospheres around Earth-sized exoplanets - which is very difficult with current technology.

Jessica Spake

The WASP-107b has been noted as one of the lowest density planets: While the planet is around the same size as Jupiter, it has just 12% of Jupiter’s mass. The exoplanet is approximately 200 light-years from Earth and takes under six days to orbit its host star.

The amount of helium found in the atmosphere of WASP-107b is so enormous that its upper atmosphere must spread tens of thousands of kilometers out into space. This also makes it the first time that an extended atmosphere has been revealed at infrared wavelengths.

As its atmosphere is widely extended, the planet is losing a substantial quantity of its atmospheric gases into space—between ~0.1-4% of its atmosphere’s total mass every billion years [2].

Way back in 2000, it was forecast that helium would be one of the most easily-detectable gases on colossal exoplanets, but up till now, searches were unproductive.

David Sing, the study’s co-author also from the University of Exeter, concludes: “Our new method, along with future telescopes such as the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, will allow us to analyze atmospheres of exoplanets in far greater detail than ever before.”

The research titled “Helium in the eroding atmosphere of an exoplanet” has been published in Nature.

Artist’s impression of WASP-107b

Artist’s impression of WASP-107b (credit: NASA, ESA)

Notes

[1] The measurement of an exoplanet’s atmosphere is performed when the planet passes in front of its host star. A tiny portion of the star’s light passes through the exoplanet’s atmosphere, leaving detectable fingerprints in the spectrum of the star. The larger the amount of an element present in the atmosphere, the easier the detection becomes.

[2] Stellar radiation has a significant effect on the rate at which a planet’s atmosphere escapes. The star WASP-107 is highly active, supporting the atmospheric loss. As the atmosphere absorbs radiation it heats up, so the gas rapidly expands and escapes more quickly into space.