Feb 19 2018

Two new research projects that used data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes suggest that the largest black holes in the universe are expanding very fast when compared to the rate of formation of stars in their galaxies.

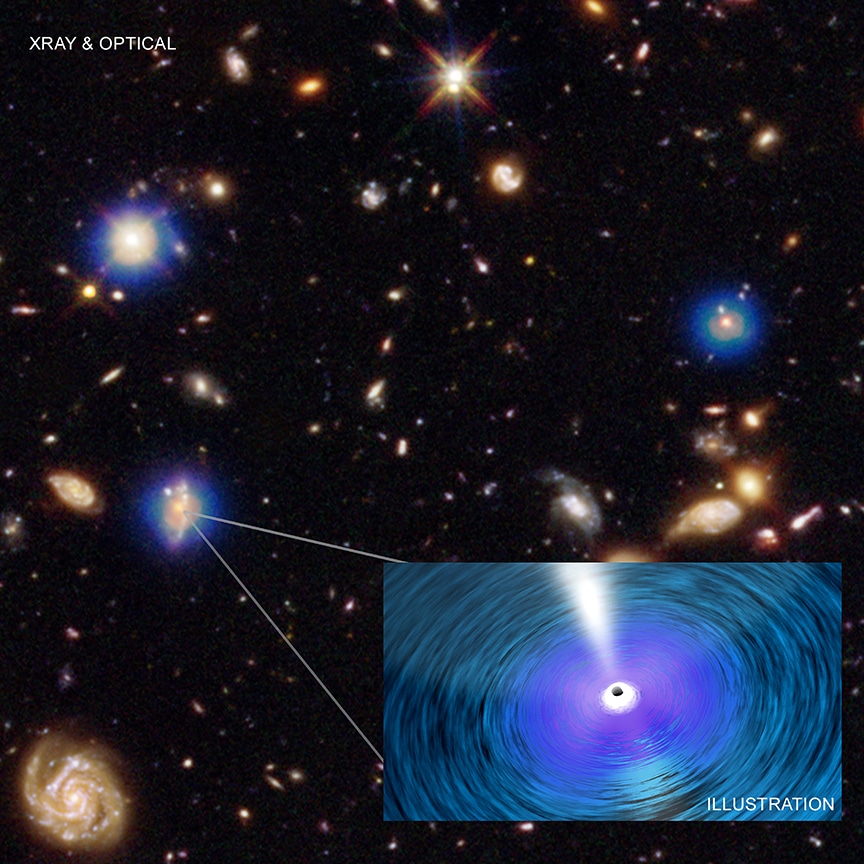

Black Holes in Chandra Deep Field South. (Image credit: NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory)

Black Holes in Chandra Deep Field South. (Image credit: NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory)

For many decades now, astronomers have collected data related to the formation of stars in galaxies as well as the expansion of supermassive black holes in their centers. The mass of supermassive black holes is with million or billion times the mass of Sun. The collected data indicated that the black holes and the stars in their galaxies expand simultaneously.

At present, outcomes of studies by scientists of two independent teams suggest that the black holes in large galaxies have expanded quite faster when compared to those in smaller galaxies.

We are trying to reconstruct a race that started billions of years ago. We are using extraordinary data taken from different telescopes to figure out how this cosmic competition unfolded.

Guang Yang - Penn State

Yang and his team used vast quantities of data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, and other observatories to investigate the expansion rate of black holes in galaxies located about 4.3-12.2 billion light-years from Earth. The X-ray data consisted of data from the Chandra Deep Field-South and North and the COSMOS-Legacy surveys.

The researchers computed the ratio between the expansion rate of a supermassive black hole and the expansion rate of stars in their own galaxy. A prevalent concept is that this ratio is roughly the same in the case of all galaxies.

In contrast, Yang and his team discovered that this ratio is considerably greater for larger galaxies. In the case of galaxies that include stars with a mass of nearly 100 billion solar masses, the ratio is close to 10 times greater than that for galaxies including stars with a mass of just 10 billion solar masses.

“An obvious question is why?” stated Niel Brandt, co-author of the study, who is also from Penn State. “Maybe massive galaxies are more effective at feeding cold gas to their central supermassive black holes than less massive ones.”

Another research team independently discovered that the expansion of most of the massive black holes has outgrown that of stars in their host galaxies. Mar Mezcua from the Institute of Space Sciences in Spain and her team investigated black holes in certain brightest and huge galaxies in the universe. They investigated 72 galaxies positioned at the center of galaxy clusters located nearly 3.5 billion light-years from Earth. They used X-ray data from Chandra and radio data from the Australia Telescope Compact Array, the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array, and Very Long Baseline Array.

Mezcua and her team predicted the masses of black holes in such galaxy clusters by adopting a familiar correlation that links the mass of a black hole to the X-ray and radio emission related to the black hole. The black hole masses were observed to be nearly 10 times huge when compared to masses predicted by another technique adopting the presumption that the black holes and galaxies expanded simultaneously.

“We found black holes that are far bigger than we expected,” stated Mezcua. “Maybe they got a head start in this race to grow, or maybe they've had an edge in speed of growth that's lasted billions of years.”

The team discovered that nearly half of the black holes in their study had masses predicted to be at least 10 billion times the mass of the Sun, positioning them in an exceptional weight class called as “ultramassive” black holes by some astronomers.

“We know that black holes are extreme objects,” stated J. Hlavacek-Larrondo of the University of Montreal, who is the co-author of the study, “so it may not come as a surprise that the most extreme examples of them would break the rules we thought they should follow.”

The study by Mezcua and her colleagues has been reported in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS) in the February 2018 issue and can be accessed online (https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.10268). The paper authored by Yang and his team has been accepted and will be published in the MNRAS in the April 2018 issue (accessible online from https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.09399).

The Chandra program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington is managed by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Chandra’s science and flight operations are controlled by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts.