Dec 12 2017

Astronomers have used two Australian radio telescopes and several optical telescopes to study complex mechanisms that are fuelling jets of material blasting away from a black hole 55 million times more massive than the Sun.

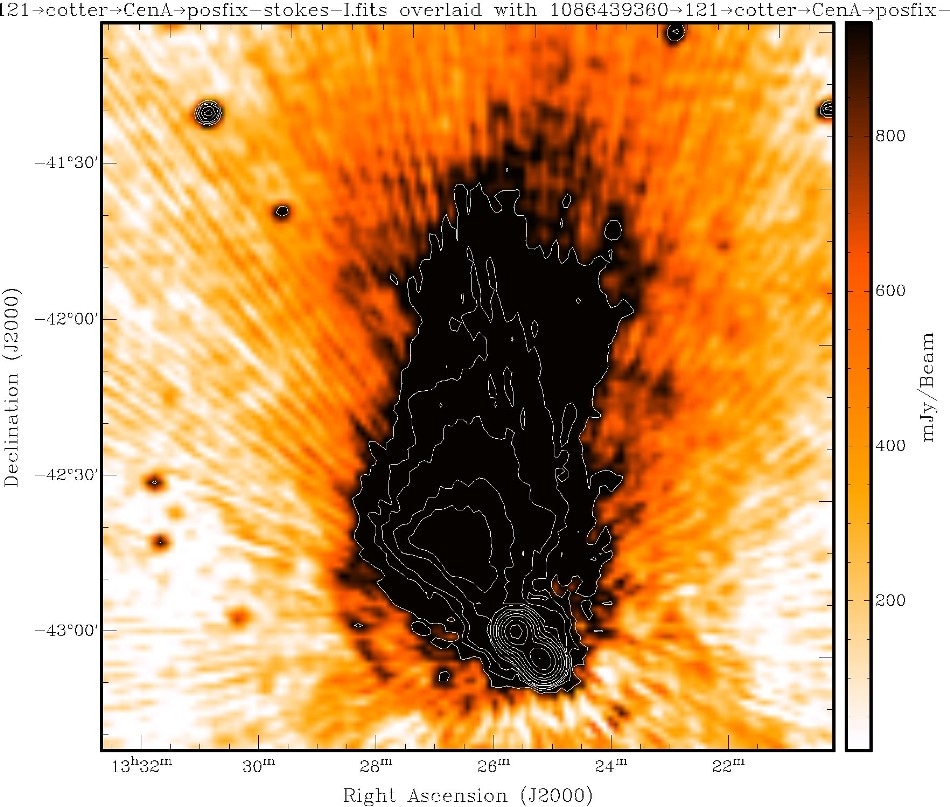

A close-up view of Centaurus A and the location of a black hole 55 million times more massive than the Sun. Credit: ICRAR/Curtin.

A close-up view of Centaurus A and the location of a black hole 55 million times more massive than the Sun. Credit: ICRAR/Curtin.

In research published today, the international team of scientists used the telescopes to observe a nearby radio galaxy known as Centaurus A.

“As the closest radio galaxy to Earth, Centaurus A is the perfect ‘cosmic laboratory’ to study the physical processes responsible for moving material and energy away from the galaxy’s core,” said Dr Ben McKinley from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) and Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia.

Centaurus A is 12 million light-years away from Earth—just down the road in astronomical terms—and is a popular target for amateur and professional astronomers in the Southern Hemisphere due to its size, elegant dust lanes, and prominent plumes of material.

“Being so close to Earth and so big actually makes studying this galaxy a real challenge because most of the telescopes capable of resolving the detail we need for this type of work have fields of view that are smaller than the area of sky Centaurus A takes up,” said Dr McKinley.

“We used the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) and Parkes—these radio telescopes both have large fields of view, allowing them to image a large portion of sky and see all of Centaurus A at once. The MWA also has superb sensitivity allowing the large-scale structure of Centaurus A to be imaged in great detail,” he said.

The MWA is a low frequency radio telescope located at the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in Western Australia’s Mid West, operated by Curtin University on behalf of an international consortium. The Parkes Observatory is 64-metre radio telescope commonly known as “the Dish” located in New South Wales and operated by CSIRO.

Observations from several optical telescopes were also used for this work— the Magellan Telescope in Chile, Terroux Observatory in Canberra, and High View Observatory in Auckland.

“If we can figure out what’s going in Centaurus A, we can apply this knowledge to our theories and simulations for how galaxies evolve throughout the entire Universe,” said co-author Professor Steven Tingay from Curtin University and ICRAR.

“As well as the plasma that’s fuelling the large plumes of material the galaxy is famous for, we found evidence of a galactic wind that’s never been seen—this is basically a high speed stream of particles moving away from the galaxy’s core, taking energy and material with it as it impacts the surrounding environment,” he said.

By comparing the radio and optical observations of the galaxy the team also found evidence that stars belonging to Centaurus A existed further out than previously thought and were possibly being affected by the winds and jets emanating from the galaxy.

The giant radio galaxy Centaurus A