Apr 2 2013

A team of astronomers led by the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) have succeeded in observing the death throws of a giant star in unprecedented detail.

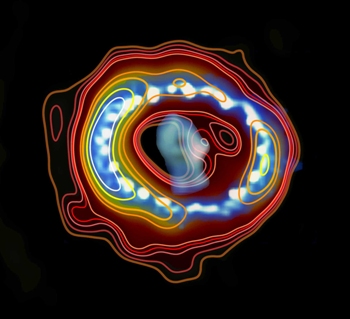

An overlay of radio emission (contours) and a Hubble space telescope image of Supernova 1987A. Credit: ICRAR (radio contours) and Hubble (image.)

An overlay of radio emission (contours) and a Hubble space telescope image of Supernova 1987A. Credit: ICRAR (radio contours) and Hubble (image.)

In February of 1987 astronomers observing the Large Magellanic Cloud, a nearby dwarf galaxy, noticed the sudden appearance of what looked like a new star. In fact they weren't watching the beginnings of a star but the end of one and the brightest supernova seen from Earth in the four centuries since the telescope was invented. By the next morning news of the discovery had spread across the globe and southern hemisphere stargazers began watching the aftermath of this enormous stellar explosion, known as a supernova.

In the two and a half decades since then, the remnant of Supernova 1987A has continued to be a focus for researchers around the world, providing a wealth of information about one of the Universe's most extreme events.

In research published in the Astrophysical Journal yesterday, a team of astronomers in Australia and Hong Kong have succeeded in using the Australia Telescope Compact Array, CSIRO radio telescope in northern New South Wales, to make the highest resolution radio images of the expanding supernova remnant at millimetre wavelengths.

"Imaging distant astronomical objects like this at wavelengths less than 1 centimetre demands the most stable atmospheric conditions. For this telescope these are usually only possible during cooler winter conditions but even then, the humidity and low elevation of the site makes things very challenging," said lead author, Dr Giovanna Zanardo of ICRAR, a joint venture of Curtin University and The University of Western Australia in Perth.

Unlike optical telescopes, a radio telescope can operate in the daytime and can peer through gas and dust allowing astronomers to see the inner workings of objects like supernova remnants, radio galaxies and black holes.

"Supernova remnants are like natural particle accelerators, the radio emission we observe comes from electrons spiralling along the magnetic field lines and emitting photons every time they turn. The higher the resolution of the images the more we can learn about the structure of this object," said Professor Lister Staveley-Smith, Deputy Director of ICRAR and CAASTRO, the Centre for All-sky Astrophysics.

Scientists study the evolution of supernovae into supernova remnants to gain an insight into the dynamics of these massive explosions and the interaction of the blast wave with the surrounding medium.

"Not only have we been able to analyse the morphology of Supernova 1987A through our high resolution imaging, we have compared it to X-ray and optical data in order to model its likely history," said Professor Bryan Gaensler, Director of CAASTRO at the University of Sydney.

The team suspects a compact source or pulsar wind nebula to be sitting in the centre of the radio emission, implying that the supernova explosion did not make the star collapse into a black hole. They will now attempt to observe further into the core and see what's there.