Apr 13 2017

All physical theories are to a greater or lesser extent, but always only simplified representations of reality and, as a consequence, have a specified range of applicability. Many scientists working on the LHCb experiment at CERN had hoped that the just achieved, exceptional accuracy in the measurement of the rare decay of the Bs0 meson would at last delineate the limits of the Standard Model, the current theory of the structure of matter, and reveal the first phenomena unknown to modern physics. Meanwhile, the spectacular result of the latest analysis has only served to extend the range of applicability of the Model.

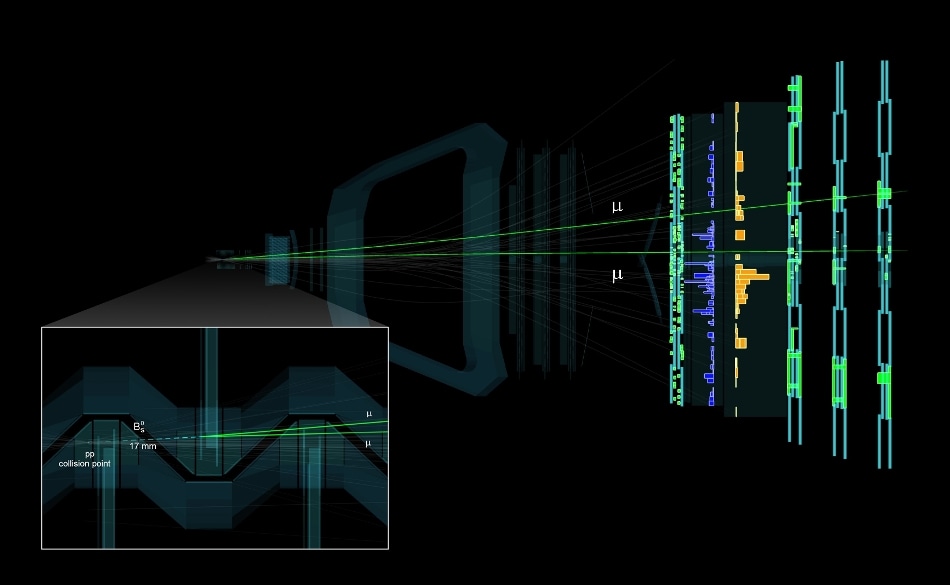

Extremely rare Bs0 meson decay into two muons, registered in 2016 at the LHCb detector at CERN near Geneva. The enlargement at the bottom shows that the point of decay was 17 mm from the collision of two protons. (Source: IFJ PAN / CERN / The LHCb Collaboration)

Extremely rare Bs0 meson decay into two muons, registered in 2016 at the LHCb detector at CERN near Geneva. The enlargement at the bottom shows that the point of decay was 17 mm from the collision of two protons. (Source: IFJ PAN / CERN / The LHCb Collaboration)

Mesons are unstable particles coming into being, among others, as a result of proton collisions in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN near Geneva. Physicists are convinced that in some very rare decays of these particles processes can potentially occur that may lead science onto the trail of new physics, with the participation of previously unknown elementary particles. It should, then, be no surprise that scientists participating in the LHCb experiment at the LHC have for a long time been looking into one of these decays: the decay of the Bs0 meson into a muon and an anti-muon. The most recent analysis, carried out for a much greater number of events than ever before, has achieved an accuracy that is exceptional for this kind of observation. The results show excellent agreement with the predictions of the Standard Model, the current theory of the constitution of matter.

“This result is a spectacular victory, only that it's slightly... pyrrhic. It is in fact one of the few cases where such great compliance of experimentation with theory, instead of being an occasion for rejoicing, slowly starts to lead to worry. Together with the improvement in the accuracy of measurement of the decays of Bs0 mesons we expected to see new phenomena, beyond the Standard Model, which we know with all certainly is not the ultimate theory. But instead of enjoying the discovery of the harbinger of a scientific revolution, we have only shown that the model is more accurate than we originally thought,” says Prof. Mariusz Witek from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Cracow.

The Standard Model is a theoretical framework constructed in the 1970s to describe phenomena occurring in the world of elementary particles. In it, matter is formed of elementary particles from a group called fermions, including quarks (down, up, strange, charm, true and beauty) and leptons (electrons, muons, tauons and their associated neutrinos). In the Model, there are also particles of antimatter, associated with their respective particles of matter. Intermediate bosons are responsible for carrying forces between fermions: photons are the carriers of electromagnetic forces, eight kinds of gluons are carriers of strong forces, and bosons W+, W- and Z0 are responsible for carrying weak forces. The Higgs boson recently discovered at the LHC gives particles mass (all of them except for gluons and photons).

Muons are elementary particles with characteristics similar to those of electrons, only around 200 times more massive. In turn, B mesons are unstable particles made up of two quarks: a beauty anti-quark and a down, up, strange or charm quark. The decay of the Bs0 meson into a muon and an anti-muon (endowed with positive electric charge) occurs extremely rarely. In the analyzed period of operation of the LHCb detector there were hundreds of trillions of proton collisions, and during each of them whole cascades of further disintegrating secondary particles were recorded. With such a large number of events in a multi-stage selection process it was only possible to pick out a few cases of this decay. One of them can be viewed in 3D at http://lhcb-public.web.cern.ch/lhcb-public/BsMuMu2017/lbevent/

In its most recent analysis the LHCb experiment team took into account not only the first but also the second phase of operation of the LHC. The larger statistics helped achieve exceptional accuracy of the measurement of the decay of the beauty meson into a muon and anti-muon, of up to 7.8 standard deviations (commonly denoted by the Greek letter sigma). In practice, this means that the probability of registering a similar result by random fluctuation is less than one to over 323 trillion.

“The spectacular measurement of the decay of the beauty meson into a muon-anti-muon pair agrees with the predictions of the Standard Model with an accuracy of up to up to nine decimal places!” emphasizes Prof. Witek.

The Standard Model has emerged victorious from another confrontation with reality. Nevertheless, physicists are confident that this is not a perfect theory. This belief stems from a number of facts. The Model does not take into account the existence of gravity, it does not explain the dominance of matter over antimatter in the contemporary universe, it offers no explanation of the nature of dark matter, it gives no answers as to the question of why fermions are composed of three groups called families. In addition, for the Standard Model to work, over 20 empirically chosen constants have to be entered into it, including the mass of each particle.

“The latest analysis significantly narrows down the values of the parameters that should be assumed by certain currently proposed extensions of the Standard Model, for example supersymmetric theories. They assume that each existing type of elementary particle has its own more massive counterpart – its superpartner. Now, as a result of the measurements, theorists dealing with supersymmetry have less and less possibility of adapting their theory to reality. Instead of coming closer, the new physics is again receding”, concludes Prof. Witek.

Physicists do not intend, however, to give up their studies of the decay of the Bs0 meson into the muon and anti-muon pair. There is still a possibility that new physics actually works here, only that its effects are smaller than expected and continue to get lost in measurement errors.