Jul 13 2016

An international collaboration led by the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (Kavli IPMU) have discovered that the color of supernovae during a specific phase could be an indicator for detecting the most distant and oldest supernovae in the Universe - more than 13 billion years old.

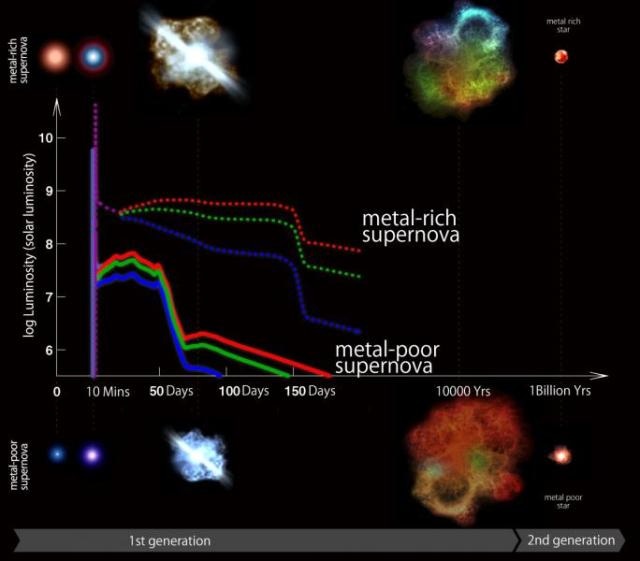

Artist's conception of evolution of metal-poor and “metal-rich” supernovae at different phases and simulated light curves from shock breakout (ultraviolet) through plateau (red, green and blue colors) to exponential decay. Both shock breakout and “plateau” phases are shorter, bluer, and fainter for metal-poor supernova in comparison with “metal-rich” supernova. (Credit: Kavli IPMU)

Artist's conception of evolution of metal-poor and “metal-rich” supernovae at different phases and simulated light curves from shock breakout (ultraviolet) through plateau (red, green and blue colors) to exponential decay. Both shock breakout and “plateau” phases are shorter, bluer, and fainter for metal-poor supernova in comparison with “metal-rich” supernova. (Credit: Kavli IPMU)

For 100 million years after the big bang, the Universe was dark and filled with hydrogen and helium. Then, the first stars appeared, and heavier elements (referred to as "metals", meaning anything heavier than helium) were created by thermonuclear fusion reactions within stars.

These metals were spread around the galaxies by supernova explosions. Studying first generation supernovae provides a glimpse into what the Universe looked like when the first stars, galaxies, and supermassive black holes formed, but to date it has been difficult to distinguish a first generation supernova from an ordinary supernova.

A new study published in The Astrophysical Journal, led by Kavli IPMU Project Researcher Alexey Tolstov, identified characteristic changes between these supernovae types after experimenting with supernovae models based on extremely metal-poor stars with virtually no metals. These stars make good candidates because they preserve their chemical abundance at the time of their formation.

“The explosions of first generation of stars have a great impact on subsequent star and galaxy formation. But first, we need a better understanding of how these explosions look like to discover this phenomenon in the near future. The most difficult thing here is the construction of reliable models based on our current studies and observations. Finding the photometric characteristics of metal poor supernovae, I am very happy to make one more step to our understanding of the early Universe.” said Tolstov.

Similar to all supernovae, the luminosity of metal-poor supernovae show a characteristic rise to a peak brightness followed by a decline. The phenomenon starts when a star explodes with a bright flash, caused by a shock wave emerging from the surface of the progenitor stars after the core collapse phase. Shock breakout is followed by a long ''plateau'' phase of almost constant luminosity lasting several months, before a slow exponential decay.

The team calculated light curves of metal-poor supernova, produced by blue supergiant stars, and “metal-rich” red supergiant stars. Both shock breakout and “plateau” phases are shorter, bluer, and fainter for metal-poor supernova in comparison with “metal-rich” supernova. The team concluded the color blue could be used as an indicator of a low-metallicity progenitor. The expanding universe makes it difficult to detect first star and supernova radiation, which shift into the near-infrared wavelength.

But in the near future new large telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to be launched in 2018, will be able to detect the first explosions of stars in the Universe, and may be able to identify them using this method. Details of this study were published on April 21, 2016.

Paper Details

Journal: Astrophysical Journal

Title: Multicolor light curve simulations of Population III core-collapse supernovae: from shock breakout to 56Co decay

Authors: Alexey Tolstov (1), Ken'ichi Nomoto (1,6), Nozomu Tominaga (2,1), Miho Ishigaki (1), Sergey Blinnikov (3,4,1), Tomoharu Suzuki (5)

Author affiliations:

1. Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (WPI), The University of Tokyo Institutes for Advanced Study, The University of Tokyo, 5-1-5 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-8583, Japan

2. Department of Physics, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Konan University, 8-9-1 Okamoto, Kobe, Hyogo 658-8501, Japan

3. Institute for Theoretical and Experimental Physics (ITEP), 117218 Moscow, Russia

4. All-Russia Research Institute of Automatics (VNIIA), 127055 Moscow, Russia

5. College of Engineering, Chubu University, 1200 Matsumoto-cho, Kasugai, Aichi 487-8501, Japan

6. Hamamatsu Professor