Feb 10 2016

Hundreds of hidden nearby galaxies have been studied for the first time, shedding light on a mysterious gravitational anomaly dubbed the Great Attractor.

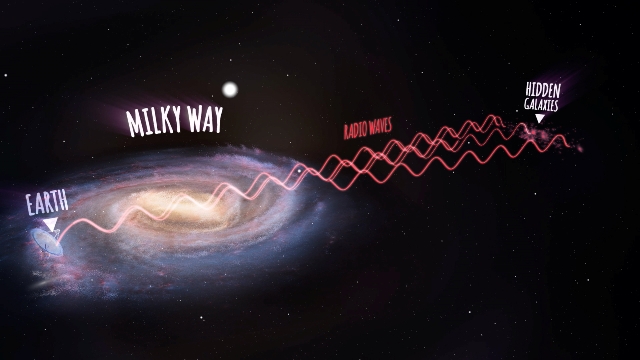

An annotated artist's impression showing radio waves travelling from the new galaxies, then passing through the Milky Way and arriving at the Parkes radio telescope on Earth (not to scale). Credit: ICRAR

An annotated artist's impression showing radio waves travelling from the new galaxies, then passing through the Milky Way and arriving at the Parkes radio telescope on Earth (not to scale). Credit: ICRAR

Despite being just 250 million light years from Earth—very close in astronomical terms—the new galaxies had been hidden from view until now by our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

Using CSIRO’s Parkes radio telescope equipped with an innovative receiver, an international team of scientists were able to see through the stars and dust of the Milky Way, into a previously unexplored region of space.

The discovery may help to explain the Great Attractor region, which appears to be drawing the Milky Way and hundreds of thousands of other galaxies towards it with a gravitational force equivalent to a million billion Suns.

Lead author Professor Lister Staveley-Smith, from The University of Western Australia node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), said the team found 883 galaxies, a third of which had never been seen before.

“The Milky Way is very beautiful of course and it’s very interesting to study our own galaxy but it completely blocks out the view of the more distant galaxies behind it,” he said.

Professor Staveley-Smith said scientists have been trying to get to the bottom of the mysterious Great Attractor since major deviations from universal expansion were first discovered in the 1970s and 1980s.

“We don’t actually understand what’s causing this gravitational acceleration on the Milky Way or where it’s coming from,” he said.

“We know that in this region there are a few very large collections of galaxies we call clusters or superclusters, and our whole Milky Way is moving towards them at more than two million kilometres per hour.”

The research identified several new structures that could help to explain the movement of the Milky Way, including three galaxy concentrations (named NW1, NW2 and NW3) and two new clusters (named CW1 and CW2).

University of Cape Town astronomer Professor Renée Kraan-Korteweg said astronomers have been trying to map the galaxy distribution hidden behind the Milky Way for decades.

“We’ve used a range of techniques but only radio observations have really succeeded in allowing us to see through the thickest foreground layer of dust and stars,” she said.

“An average galaxy contains 100 billion stars, so finding hundreds of new galaxies hidden behind the Milky Way points to a lot of mass we didn't know about until now.”

Dr. Bärbel Koribalski from CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science said innovative technologies on the Parkes Radio telescope had made it possible to survey large areas of the sky very quickly.

“With the 21-cm multibeam receiver on Parkes we’re able to map the sky 13 times faster than we could before and make new discoveries at a much greater rate,” she said.

The study involved researchers from Australia, South Africa, the US and the Netherlands, and was published today in the Astronomical Journal.

More information:

The International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) is a joint venture between Curtin University and The University of Western Australia with support and funding from the State Government of Western Australia.

Professor Lister Staveley-Smith is ICRAR’s Director of Science at UWA and the Deputy Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO).

Dr Bärbel S. Koribalski is a CSIRO Science Leader, leading the HI group at CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science. Dr Koribalski and Prof Staveley-Smith are the principal investigators of WALLABY, the ASKAP HI All-Sky Survey.

The ‘Great Attractor’ is a diffuse concentration of mass 250 million light-years away, that’s pulling our galaxy, the Milky Way, and hundreds of thousands of other galaxies towards it.

CSIRO’s Parkes telescope, or “the Dish”, is a 64-metre radio telescope located in New South Wales, Australia. The telescope has been in operation since 1961 and continues to be at the forefront of astronomical discovery.