Dec 2 2014

Nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamonds could be used to construct vital components for quantum computers. But hitherto it has been impossible to read optically written information from such systems electronically.

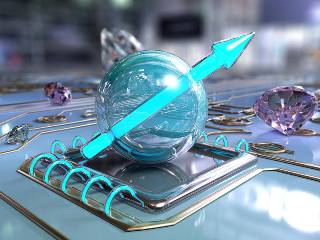

Vision of a future quantum computer with chips made of diamond and graphene - Image: Christoph Hohmann / NIM

Vision of a future quantum computer with chips made of diamond and graphene - Image: Christoph Hohmann / NIM

Using a graphene layer, a team of scientists headed by Professor Alexander Holleitner of the Technische Universität München (TUM) has now implemented just such a read unit.

Ideally, diamonds consist of pure carbon. But natural diamonds always contain defects. The most researched defects are nitrogen-vacancy centers comprising a nitrogen atom and a vacancy. These might serve as highly sensitive sensors or as register components for quantum computers. However, until now it has not been possible to extract the optically stored information electronically.

A team headed by Professor Alexander Holleitner, physicist at the TU München and Frank Koppens, physics professor at the Institut de Ciencies Fotoniques near Barcelona, have now devised just such a methodology for reading the stored information. The technique builds on a direct transfer of energy from nitrogen-vacancy centers in nanodiamonds to a directly neighboring graphene layer.

Non-radiative energy transfer

When laser light shines on a nanodiamond, a light photon raises an electron from its ground state to an excited state in the nitrogen-vacancy center. “The system of the excited electron and the vacated ground state can be viewed as a dipole,” says Professor Alexander Holleitner. “This dipole, in turn, induces another dipole comprising an electron and a vacancy in the neighboring graphene layer.”

In contrast to the approximately 100 nanometer large diamonds, in which individual nitrogen-vacancy centers are insulated from each other, the graphene layer is electrically conducting. Two gold electrodes detect the induced charge, making it electronically measureable.

Picosecond electronic detection

Essential for this experimental setup is that the measurement is made extremely quickly, because the generated electron-vacancy pairs disappear after only a few billionths of a second. However, the technology developed in Holleitners laboratory allows measurements in the picosecond domain (trillionths of a second). The scientists can thus observe these processes very closely.

“In principle our technology should also work with dye molecules,” says doctoral candidate Andreas Brenneis, who carried out the measurements in collaboration with Louis Gaudreau. “A diamond has some 500 point defects, but the methodology is so sensitive that we should be able to even measure individual dye molecules.”

As a result of the extremely fast switching speeds of the nanocircuits developed by the researchers, sensors built using this technology could be used not only to measure extremely fast processes. Integrated into future quantum computers they would allow clock speeds ranging into the terahertz domain.