Sep 15 2014

Blowing bubbles may be fun for kids, but for engineers, bubbles can disrupt fluid flow and damage metal.

Researchers from the Fuels, Engines and Emissions Research Center at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and collaborators from ORNL’s High Flux Isotope Reactor – a DOE Office of Science User Facility – are using neutrons to study the formation of these damage-causing bubbles in fuel injectors.

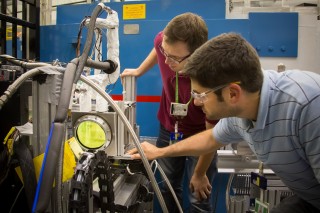

Derek Splitter and Eric Nafziger from the Fuels, Engines and Emissions Research Center at Oak Ridge National Laboratory prepare their fuel injector test system for experiments at the High Flux Isotope Reactor. They used the neutron beam at HFIR to non-destructively study the internal structure of fuel injectors for gasoline vehicles so that the internal fluid flow could be modeled based on the imaged components. Source: Genevieve Martin/ORNL

Derek Splitter and Eric Nafziger from the Fuels, Engines and Emissions Research Center at Oak Ridge National Laboratory prepare their fuel injector test system for experiments at the High Flux Isotope Reactor. They used the neutron beam at HFIR to non-destructively study the internal structure of fuel injectors for gasoline vehicles so that the internal fluid flow could be modeled based on the imaged components. Source: Genevieve Martin/ORNL

This team is attempting to make the first-ever neutron images of cavitation, the physical event that leads to bubble/gas formation, inside the body of a gasoline fuel injector. In August, they conducted their research at HFIR’s CG-1D beam line, which is used for neutron radiography and computed tomography, to non-destructively study the internal structure of the fuel injector. With data in hand, they will be diving deep into the analysis of the images to identify both the location and the timing of the cavitation.

“We can measure the spray of a fuel injector using X-rays, but imaging the internal structure in operation is very challenging,” said Hassina Bilheux, HFIR instrument scientist for CG-1D.

The team, led by Eric Nafziger, Derek Splitter and Todd Toops from FEERC/ORNL under a Laboratory Directed Research and Development project, studied a spray-guided gasoline direct-injection (SGDI) unmodified 6-hole injector. SGDI systems are a relatively new technology that have been developed to more precisely control fuel delivery to each cylinder and allow reduced fuel consumption in gasoline engines.

“There's a lot that is not understood about these systems, and thus a lot to be learned,” Toops said. “Our work is focused on identifying the time and location of cavitation events – to study the injector with the ability to see cavitation in action.”

A cavitation event is when a gas bubble forms in the injectors, disrupting the spray pattern and ultimately deteriorating the injector material properties.

“Neutrons are ideally suited for this study due to their high sensitivity to hydrogen atoms in the fuel and low interactions with the metal part of the injector,” said Bilheux.

Other complementary research has been done with lasers, X-rays and even with fuel injectors made partially with acrylic to make them see-through. However, those experiments had temperature and pressure limitations. This neutron technique, explained Toops, is the first to have the potential to see what’s happening inside the injector at normal operating conditions.

In order to create an experiment that closely mimics natural conditions of an engine running, Nafziger, Splitter and Toops developed a closed loop fuel injection system designed to operate with commercial and prototype injectors and deliver fuel to the injectors at pressures up to 120 atmospheres.

With 48 hours of observations for a given operating condition, they compiled approximately 1 million injection events to capture a 7 millisecond composite injection sequence, with 1 millisecond before injection, 1 millisecond of injection, and 5 milliseconds after injection. This compilation was accomplished with a 0.02 millisecond time resolution.

“In the initial analysis of the composite neutron images, it is possible to see both internal injector motion and the spray exiting the nozzle,” said Nafziger. “Just inside the nozzle area, a marked difference in fluid density is also observed during the injection event, indicating vaporization of the fluid and possible cavitation.”

The team is working on more detailed analysis of the data, and will collaborate with the ORNL high performance computing team for fluid dynamics modeling as part of the second year of their project.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for the Department of Energy’s Office of Science. DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of the time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.