May 8 2014

A team of scientists at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., has successfully reproduced, right here on Earth, the processes that occur in the atmosphere of a red giant star and lead to the formation of planet-forming interstellar dust.

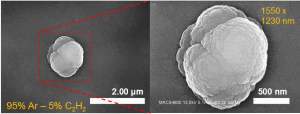

Scanning Electron Microscope image of a large (approximately 1.5 micrometer diameter) aggregate of nanograins produced in the Cosmic Simulation Chamber at NASA's Ames Research Center, using a 95 percent Ar – 5% C2H2 gas mixture. The nanograins and aggregates are deposited onto ultra-high vacuum aluminum foil. Image Credit: NASA/Ames/Farid Salama

Scanning Electron Microscope image of a large (approximately 1.5 micrometer diameter) aggregate of nanograins produced in the Cosmic Simulation Chamber at NASA's Ames Research Center, using a 95 percent Ar – 5% C2H2 gas mixture. The nanograins and aggregates are deposited onto ultra-high vacuum aluminum foil. Image Credit: NASA/Ames/Farid Salama

Using a specialized facility, called the Cosmic Simulation Chamber (COSmIC) designed and built at Ames, scientists now are able to recreate and study in the laboratory dust grains similar to the grains that form in the outer layers of dying stars. Scientists plan to use the dust to gather clues to better understand the composition and the evolution of the universe.

Dust grains that form around dying stars and are ejected into the interstellar medium lead, after a life cycle spanning millions of years, to the formation of planets and are a key component of the universe's evolution. Scientists have found the materials that make up the building blocks of the universe are much more complicated than originally anticipated.

"The harsh conditions of space are extremely difficult to reproduce in the laboratory, and have long hindered efforts to interpret and analyze observations from space," said Farid Salama, project leader and a space science researcher at Ames. "Using the COSmIC simulator we can now discover clues to questions about the composition and the evolution of the universe, both major objectives of NASA's space research program."

In the past, the inability to simulate space conditions in the gaseous state prevented scientists from identifying unknown matter. Because conditions in space are vastly different from conditions on Earth, it is challenging to identify extraterrestrial materials. Thanks to COSmIC, researchers can successfully simulate gas-phase environments similar to interstellar clouds, stellar envelopes or planetary atmospheres environments by expanding gases using a cold jet spray of argon gas seeded with hydrocarbons that cools down the molecules to temperatures representative of these environments.

COSmIC integrates a variety of state-of-the-art instruments to allow scientists to recreate space conditions in the laboratory to form, process and monitor simulated planetary and interstellar materials. The chamber is the heart of the system. It recreates the extreme conditions that reign in space where interstellar molecules and ions float in a vacuum at densities that are billionths of Earth's atmosphere, average temperatures can be less than -270 degrees Fahrenheit (about 100 degrees Kelvin), and the environment is bathed in ultraviolet and visible radiation emanating from nearby stars.

"By using COSmIC and building up on the work we recently published in the Astrophysical Journal August 29, 2013, we now can for the first time truly recreate and visualize in the laboratory the formation of carbon grains in the envelope of stars and learn about the formation, structure and size distribution of stellar dust grains," said Cesar Contreras of the Bay Area Environmental Research (BAER) Institute and a research fellow at Ames. "This type of new research truly pushes the frontiers of science toward new horizons, and illustrates NASA's important contribution to science."

The team started with small hydrocarbon molecules that it expanded in the cold jet spray in COSmIC and exposed to high energy in an electric discharge. They detected and characterized the large molecules that are formed in the gas phase from these precursor molecules with highly sensitive detectors, then collected the individual solid grains formed from these complex molecules and imaged them using Ames' Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).

"During COSmIC experiments, we are able to form and detect nanoparticles on the order of 10 nm size, grains ranging from 100-500 nanometers and aggregates of grains up to 1.5 micrometers in diameter, about a tenth the width of a human hair, and observe their structure with SEM, thus sampling a large size distribution of the grains produced," said Ella Sciamma-O'Brien, of the BAER Institute and a research fellow at Ames.

These results have important implications and ramifications not only for interstellar astrophysics, but also for planetary science. For example, they can provide new clues on the type of grains present in the dust around stars. That in turn, will help us understand the formation of planets, including Earth-like planets. They also will help interpret astronomical data from the Herschel Space Observatory, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) and the ground-based Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array observatory in Chile.

"Today we are celebrating a major milestone in our understanding of the formation and the nature of cosmic dust grains that bears important implications in this new era of exoplanets discoveries," concluded Salama.

This work is funded through the Laboratory Astrophysics Carbon-in-the-Galaxy consortium program, an element of the Astrophysics Division's Astrophysics Research and Analysis program in NASA's Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington and is supported by Ames' Advanced Studies Laboratories, a partnership between Ames and the University of California in Santa Cruz.

For more information about COSmIC, visit: http://go.nasa.gov/ioHkeS

For more information about Ames, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/ames