Mar 25 2014

Draining the water from a bathtub causes a spinning tornado to appear. The downward flow of water into the drain causes the water to rotate, and as the rotation speeds up, a vortex forms that obeys the laws of classical mechanics. However, if the water is extremely cold liquid helium, the fluid will swirl around an invisible line to form a vortex that obeys the laws of quantum mechanics.

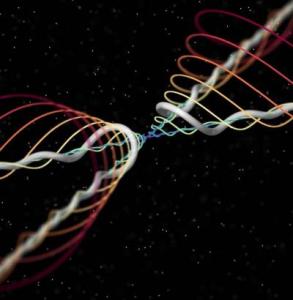

Sometimes, two of these quantum tornadoes flex into curved lines, cross over one another to form a letter X shape, swap ends, and then violently retract from one another—a process called reconnection.

Illustration of Kelvin waves on retracting quantized vortices after they met, crossed and exchanged tails -- a process called reconnection. A new study provides visual evidence that after the vortexes snap away from each other, they develop ripples called "Kelvin waves" to quickly get rid of the energy caused by the connection and relax the system. Credit: Enrico Fonda

Illustration of Kelvin waves on retracting quantized vortices after they met, crossed and exchanged tails -- a process called reconnection. A new study provides visual evidence that after the vortexes snap away from each other, they develop ripples called "Kelvin waves" to quickly get rid of the energy caused by the connection and relax the system. Credit: Enrico Fonda

Computer simulations have suggested that after the vortexes snap away from each other, they develop ripples called "Kelvin waves" to quickly get rid of the energy caused by the connection and relax the system. However, the existence of these waves had never been experimentally proven.

Now, for the first time, researchers provide visual evidence confirming that the reconnection of quantum vortexes launches Kelvin waves. The study, which was conducted at the University of Maryland, will be published the week of March 24, 2014 in the online early edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation.

"We weren't surprised to see the Kelvin waves on the quantum vortex, but we were excited to see them because they had never been seen before," said Daniel Lathrop, a UMD physics professor. "Seeing the Kelvin waves provided the first experimental evidence that previous theories predicting they would be launched from vortex reconnection were correct."

Understanding turbulence in quantum fluids, such as ultracold liquid helium, may offer clues to neutron stars, trapped atom systems and superconductors. Superconductors, which are materials that conduct electricity without resistance below certain temperatures, develop quantized vortices. Understanding the behavior of the vortices may help researchers develop superconductors that remain superconducting at higher current densities.

Physicists Richard Feynman and Lars Onsager predicted the existence of quantum vortices more than a half-century ago. However, no one had seen quantum vortices until 2006. In Lathrop's laboratory at UMD, researchers prepared a cylinder of supercold helium—at 2 degrees Celsius above absolute zero—injected with frozen tracer particles made from atmospheric air and helium gases. When they shined a laser into the cylinder, the researchers saw the particles trapped on the vortices like dew drops on a spider web.

"Kelvin waves on quantized vortices had been predicted, but the experiments were challenging because we had to conduct them at lower temperatures than our previous experiments," explained Lathrop.

Since 2006, the researchers have used the same technique to further examine quantum vortexes. During an experiment in February 2012, they witnessed a unique reconnection event. One vortex reconnected with another and a wave propagated down the vortex. To quantitatively study the wave's motion, the researchers tracked the position of the particles on the vortex. The resulting waveforms agreed generally with theories of Kelvin waves propagating from quantum vortexes.

"These first observations of Kelvin waves will surely lead to exciting new experiments that push the limits of our knowledge of these exotic quantum motions," added Lathrop.

In the future, Lathrop plans to use florescent nanoparticles to investigate what happens near the transition to the superfluid state.

Lathrop conducted the current study with David Meichle, a UMD physics graduate student; Enrico Fonda, who was a research scholar at UMD and graduate student at the University of Trieste when the study was performed and is now a postdoctoral researcher at New York University; Nicholas Ouellette, who was a visiting assistant professor at UMD when the study was performed and is now an associate professor in mechanical engineering & materials science at Yale University; and Sahand Hormoz, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara's Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics.