Mar 13 2014

Light waves have the potential to boost the efficiency of conventional electronics by a factor of 100,000. In a review article that appears in “Nature Photonics” on March 14th, Prof. Ferenc Krausz of the Laboratory for Attosecond Physics (LAP) at the Max-Planck-Institut für Quantenoptik and the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München and his co-author Prof. Mark Stockman of Georgia State University (GSU) in Atlanta describe how this vision may one day come true.

In their scenario, one would exploit the electric field of laser light to control the flow of electrons in dielectric materials, which, in turn, may modulate transmitted light and switch current in electronic circuits at light frequencies. Visible light oscillates at frequencies of about 1015 cycles per second, opening the possibility of switching light or electric current at rates in this range. And since both signals can also carry information, innovative optoelectronic technologies would enable a corresponding increase in the speed of data processing, opening a new era in information technology. The authors review the novel tools and techniques of attosecond technology, which may play a crucial role in making the above advances actually happen.

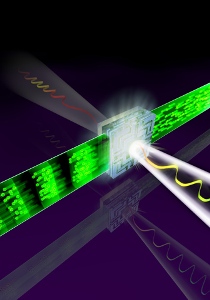

In the future it might be possible, that electric currents (green) will be switched with the frequencies of light waves (up to the peta-hertz region) that are bouncing on a chip. (Graphic: Christian Hackenberger)

In the future it might be possible, that electric currents (green) will be switched with the frequencies of light waves (up to the peta-hertz region) that are bouncing on a chip. (Graphic: Christian Hackenberger)

Light is likely to become the tool of choice for controlling electric currents and data processing. After all, its electric field directs the behavior of electrons, which are the stuff of electric current and encode the information in our computer and communications networks. The ability to manipulate electrons with light would open up a new era by permitting switching rates of 1015 per second, for light waves oscillate at frequencies of that order.

But turning this vision into a reality will require essentially perfect control over the properties of light waves. In a new review article in Nature Photonics, Ferenc Krausz and his American colleague Mark Stockman (a specialist in solid-state physics) discuss their visionary concepts and point to possible ways of achieving this goal. Their ideas are based on initial theoretical and experimental investigations which suggest that the oscillating electric field of light may switch electric current (doi:10.1038/nature11567) and modulate light (doi:10.1038/nature11720) flowing in and transmitted/reflected by solid-state devices, respectively (Nature, 3 January 2013). This type of interaction between optical fields and electrons provides the technical basis for the field of attosecond physics, and has made it possible for the first time to observe the motions of electrons within atoms in real time, with the aid of attosecond light flashes. An attosecond is a billionth (10-9) of a billionth of a second, in other words 1018 times shorter than a second. Moreover, one can precisely mold the shape of these attosecond flashes (i.e. how their intensity varies with time), provided one has exquisite control over the behavior of the lasers that produce them. In their article, Krausz and Stockmann describe the techniques that have been developed to accomplish this feat. A more detailed history of attosecond physics is available on LAP’s homepage (https://www.attoworld.de/).

The new issue of Nature Photonics also includes a report on the latest work done by Prof. Krausz and his team, in collaboration with Mark Stockman and Vadym Apalkov from GSU. They have shown that the current generated in an insulating material (silica) by the electric field of an intense and ultrashort laser pulse provides information about the precise waveform of the pulse that produced it (doi:10.1038/nphoton.2013.348, Nature Photonics, 14 March 2013). This finding represents the first step towards the realization of a detector that can visualize the shape of light waves, just as an oscilloscope “reproduces” microwaves. This breakthrough means that attosecond technology is at least on course to extend the domain of electron metrology into the optical frequency range. Whether or not this will lead to a corresponding increase in signal processing rates remains an open question. “Our goal is to develop a chip that allows us to switch electric currents on and off at optical frequencies. This would increase rates of information processing by a factor of 100,000, and that is as fast as it gets.” The published experiments are still in the realm of basic research. But the scientists have begun to breach the limits of conventional electronics and photonics, thus opening the route to a far more efficient, light-based, electronics. Thorsten Naeser