Nov 3 2012

Like a Hollywood starlet constantly retouching her make-up, the giant asteroid Vesta is constantly stirring its outermost layer and presenting a young face. Data from NASA's Dawn mission show that a common form of weathering, which occurs on many airless bodies in the inner solar system like the Moon, does not age Vesta's outermost layer.

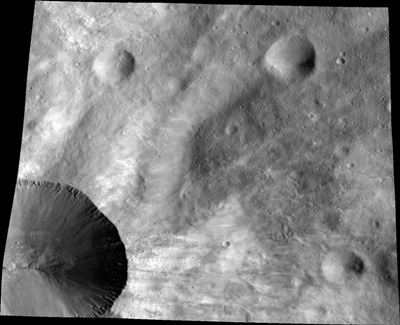

This image from NASA's Dawn spacecraft shows a close up of part of the rim around the crater Canuleia on the giant asteroid Vesta. Canuleia, about 6 miles (10 kilometers) in diameter, is the large crater at the bottom-left of this image. This close-up image illustrates the structure of the interior of the crater and complex details of the fresh rays across the soil of Vesta. The image was taken by Dawn's framing camera on Dec. 29, 2011, from an altitude of about 130 miles (210 kilometers). Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/PSI/Brown

This image from NASA's Dawn spacecraft shows a close up of part of the rim around the crater Canuleia on the giant asteroid Vesta. Canuleia, about 6 miles (10 kilometers) in diameter, is the large crater at the bottom-left of this image. This close-up image illustrates the structure of the interior of the crater and complex details of the fresh rays across the soil of Vesta. The image was taken by Dawn's framing camera on Dec. 29, 2011, from an altitude of about 130 miles (210 kilometers). Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/PSI/Brown

Carbon-rich asteroids have also been splattering dark material on Vesta's surface over a long span of its history. The results are described in two papers reported on Nov. 1 in the journal Nature.

David Williams, an associate research professor in ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration, is a co-author of the Nature article on Vesta's dark material, titled "Dark Material on Vesta: Delivering Carbonaceous Volatile-Rich Materials to Planetary Surfaces."

"The dark material on Vesta has been a perplexing problem, one we first noticed as Dawn approached Vesta in the summer of 2011," said Williams, a member of the science team task force investigating the dark material. "Through Dawn's mission at Vesta, it became clear that the dark material was mostly derived from carbon-rich asteroids that impacted Vesta's surface."

Early pictures of Vesta showed a variety of dramatic light and dark splotches on its surface. These light and dark materials were unexpected and show Vesta has a brightness range that is among the largest observed on rocky bodies in our solar system.

"Most of the smaller dark material patches are associated with impact craters, forming dark rays of ejecta spreading outward," Williams said. "There are also large regions of dark material, whose composition suggests they are derived from carbon-rich asteroids - perhaps from one or more large impacts early in Vesta's history."

Dawn scientists suspected early on that bright material is native to Vesta. One of their first theories for the dark material suggested it might come from the shock of high-speed impacts melting and darkening the underlying rocks or from recent volcanic activity.

An analysis of data from Dawn's visible and infrared mapping spectrometer and the framing camera revealed that distribution of dark material is widespread and occurs in small spots and in diffuse deposits, without correlation to any particular underlying geology. The likely source of the dark material is now shown to be carbon-rich asteroids, which are also believed to have deposited hydrated minerals on Vesta.

To get the amount of darkening we now see on Vesta, Williams and colleagues said, scientists estimate about 300 dark asteroids with diameters between 0.6 to 6 miles (1 and 10 kilometers) likely hit Vesta during the last 3.5 billion years. This would have been enough to wrap Vesta in a blanket of mixed material 3 to 7 feet (1 to 2 meters) thick.

"This perpetual contamination of Vesta with material from elsewhere in the solar system is a dramatic example of an apparently common process that changes many solar system objects," said Thomas McCord, lead author of the Nature paper, who worked with Williams on this study. "Earth likely got the ingredients for life - organics and water - this way."

Launched in 2007, Dawn spent more than a year investigating Vesta. It departed in September 2012 and is currently on its way to the dwarf planet Ceres.

Williams is a participating scientist on NASA's Dawn mission. JPL manages the Dawn mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Dawn is a project of the directorate's Discovery Program, managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. The University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) is responsible for overall Dawn mission science.

Orbital Sciences Corp., Dulles, Va., designed and built the spacecraft. The German Aerospace Center, the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, the Italian Space Agency and the Italian National Astrophysical Institute are international partners on the mission team. The California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, manages JPL for NASA.