Feb 13 2014

It's not quite Star Trek communications—yet. But long-distance communications in space may be easier now that researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) have designed a clever detector array that can extract more information than usual from single particles of light.

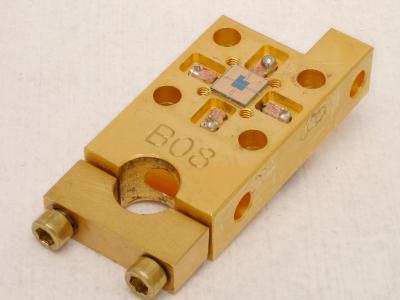

This NIST device, 1.5 by 3 centimeters in outer dimensions, is a prototype receiver for laser communications enabling much higher data rates than conventional systems. Superconducting detectors in the center of the small square chip register the timing and position of single particles of light. Credit: Verma and Tomlin/NIST

This NIST device, 1.5 by 3 centimeters in outer dimensions, is a prototype receiver for laser communications enabling much higher data rates than conventional systems. Superconducting detectors in the center of the small square chip register the timing and position of single particles of light. Credit: Verma and Tomlin/NIST

Described in a new paper,* the NIST/JPL array-on-a-chip easily identifies the position of the exact detector in a multi-detector system that absorbs an incoming infrared light particle, or photon. That's the norm for digital photography cameras, of course, but a significant improvement in these astonishingly sensitive detectors that can register a single photon. The new device also records the signal timing, as these particular single-photon detectors have always done.

The technology could be useful in optical communications in space. Lasers can transmit only very low light levels across vast distances, so signals need to contain as much information as possible.

One solution is "pulse position modulation" in which a photon is transmitted at different times and positions to encode more than the usual one bit of information. If a light source transmitted photons slightly to the left/right and up/down, for instance, then the new NIST/JPL detector array circuit could decipher the two bits of information encoded in the spatial position of the photon. Additional bits of information could be encoded by using the arrival time of the photon.

The same NIST/JPL collaboration recently produced detector arrays for the first demonstration of two-way laser communications outside Earth's orbit using the timing version of pulse position modulation.** The new NIST/JPL paper shows how to make an even larger array of detectors for future communications systems.

The new technology uses superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors. The current design can count tens of millions of photons per second but the researchers say it could be scaled up to a system capable of counting of nearly a billion photons per second with low dark (false) counts. The key innovation enabling the latest device was NIST's 2011 introduction of a new detector material, tungsten-silicide, which boosted efficiency, the ability to generate an electrical signal for each arriving photon.*** Detector efficiency now exceeds 90 percent. Other materials are less efficient and would be more difficult to incorporate into complex circuits.

The detectors superconduct at cryogenic temperatures (about minus 270 °C or minus 454 °F), and cooling needs set a limit on wiring complexity. The NIST/JPL scheme requires only twice as many wires (2N) as the number of detectors on one side of a square array (N x N), greatly reducing cooling loads compared to a one-wire-per-detector approach while maintaining high timing accuracy. NIST researchers demonstrated the scheme for a four-detector array with four wires and are now working on a 64-detector array with 16 wires.

In the circuit, each detector is located in a specific column and row of the square array. Each detector acts like an electrical switch. When the detector is in the superconducting state, the switch is closed and the current is equally distributed among all detectors in that column. When a detector absorbs a photon, the switch opens, temporarily diverting the current to an amplifier for the affected column while reducing the signal through the affected row. As a result, the circuit generates a voltage spike in the column readout and a voltage dip in the row readout. The active detector is at the intersection of the active column and row.