Dec 17 2013

An international team led from the University of Leicester has published a major list of celestial X-ray sources in the Astrophysical Journal. The result of many years work, this list of over 150,000 high-energy stars and galaxies will be a vital resource for future astronomical studies.

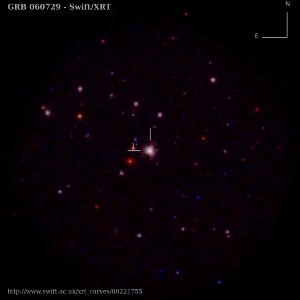

An image of the X-ray sky centred on a gamma-ray burst which exploded on the 29th of July 2006. The image is almost half a degree across, the same size as the full Moon. In this very long exposure of one million seconds many celestial X-ray sources can be seen, they are colour coded according to their X-ray colour (red for low energy X-rays, blue for higher energies). Image credit: Evans (University of Leicester)

An image of the X-ray sky centred on a gamma-ray burst which exploded on the 29th of July 2006. The image is almost half a degree across, the same size as the full Moon. In this very long exposure of one million seconds many celestial X-ray sources can be seen, they are colour coded according to their X-ray colour (red for low energy X-rays, blue for higher energies). Image credit: Evans (University of Leicester)

Using the X-ray telescope on board the US/UK/Italian Swift satellite, the team analysed eight years’ worth of data to make the first Swift X-ray Point Source catalogue. In addition to providing the positions of almost a hundred thousand previously unknown X-ray sources, the team have also analysed the X-ray variability and X-ray colours of the sources in order to help to understand the origin of their emission, and to help in the classification of rare and exotic objects. All of the data, including light curves and spectra are available online.

The NASA Swift satellite was launched in November 2004 to study gamma-ray bursts: hugely powerful stellar explosions which can be seen back to the time when the Universe was only a few percent of its current age. Swift has been one of the most productive astronomical facilities since it was launched, and has revolutionised GRB research. The X-ray telescope on Swift has played a key role in these discoveries, but as well as finding the afterglows of GRBs it also sees many other unrelated X-ray sources that are serendipitously in the telescope’s field of view. In order to be able to respond quickly to the rapidly fading GRBs, Swift is uniquely agile and autonomous, able to point within a minute or so at a new target. Because of its science remit and this unusual ability, the Swift XRT has observed a much larger fraction of the sky than the larger European and US X-ray observatories. For this reason it has found a vast number of extra sources in spite of its much lower cost.

Stars and galaxies emit X-rays because the electrons in them move at extremely high speeds, either because they are very hot (over a million degrees) or because extreme magnetic fields accelerate them. The underlying cause is usually gravity; gas can be compressed and heated as it falls on to black holes, neutron stars and white dwarfs or when trapped in the turbulent magnetic fields of stars like our Sun. Most of the newly discovered X-ray sources are expected to signal the presence of super-massive black holes in the centres of large galaxies many millions of light-years from earth, but the catalogue also contains transient objects (short-lived bursts of X-ray emission) which may come from stellar flares or supernovae.

The X-ray camera used in this work was built at the University of Leicester, following a 50-year tradition there of providing sensitive equipment for launch into space. The camera used a spare CCD from a previous instrument to save costs; these CCDs are like those used in a digital camera, but have a design optimised for X-ray detection. The University of Leicester supports the efficient operation of the camera in flight, and runs a scientific data centre providing Swift results to the world within minutes of the observation.

First author, Dr Phil Evans of the Department of Physics and Astronomy said: “The unique way Swift works has allowed us to produce not just another catalogue of X-ray objects, but one with a real insight into how celestial X-ray emission varies with time. Astronomers will use this for years ahead when trying to understand the new things they see.”

The leader of the Swift team at Leicester, and second author, Professor Julian Osborne said: “Catalogues of stars and galaxies form the bedrock of the work of astronomers. The culmination of great effort, they are a valuable resource for understanding the Universe, and frequently go on to be used in ways which could not be imagined when they are made.”

Swift continues to observe GRBs and other celestial X-ray sources. Relying only on sunlight for power, it is expected to continue to operate for many years to come. The Swift X-ray Point Source catalogue will be updated in a few years’ time.