Dec 6 2013

JILA researchers have developed a method of spinning electric and magnetic fields around trapped molecular ions to measure whether the ions' tiny electrons are truly round—research with major implications for future scientific understanding of the universe.

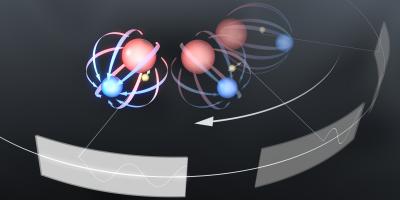

This is an artist's conception of JILA's new technique for measuring the electron's roundness, or electric dipole moment (EDM). The method involves trapping molecular ions of hafnium fluoride (red and blue spheres, respectively) in spinning electric and magnetic fields. Researchers measure changes over time in the "spin" direction of the molecules' unpaired electrons (arrows in yellow spheres), which act like tiny bar magnets. Specific patterns in the rate of change, reflecting alterations in the gap between two magnetic energy levels in the molecules, would indicate the existence and size of an EDM. Credit: Baxley/JILA

This is an artist's conception of JILA's new technique for measuring the electron's roundness, or electric dipole moment (EDM). The method involves trapping molecular ions of hafnium fluoride (red and blue spheres, respectively) in spinning electric and magnetic fields. Researchers measure changes over time in the "spin" direction of the molecules' unpaired electrons (arrows in yellow spheres), which act like tiny bar magnets. Specific patterns in the rate of change, reflecting alterations in the gap between two magnetic energy levels in the molecules, would indicate the existence and size of an EDM. Credit: Baxley/JILA

As described in the Dec. 6, 2013, issue of Science,* the JILA team used their new spinning method to make their first measurement of the electron's roundness—technically, the electron's electric dipole moment (eEDM), a measure of the uniformity of the electron's charge between its poles. The JILA team's measurement is not yet as precise as eEDM measurements made by other groups. But the main purpose of the research at this time is to demonstrate a powerful new technique that may eventually provide the best eEDM measurements, and may also be useful in quantum information and simulation experiments.

JILA is a joint institute of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder.

JILA/NIST Fellow Eric Cornell says his quest to measure the eEDM—5 years and counting—is as challenging as looking for a single virus particle on an object the size of Earth.

"Our paper presents a new method for getting to a better limit" on the electron's electric dipole moment, Cornell says. "Our hope is eventually to leapfrog over existing limits and get a still better result, but that will be at least a couple years out."

Decades ago, physicists believed the electron was perfectly round. In the 1980s, the idea of a slight asymmetry became acceptable, but any eEDM was thought to be too tiny to see. Some current theories predict that the eEDM might be only a bit smaller than the latest measurements indicate and might arise from exotic, as-yet-unknown particles.

Scientists are now trying to push the limits of eEDM measurements to either validate or disprove some of the competing theories. The current experimental upper limit is much, much larger than the eEDM predicted by the Standard Model of physics. But extensions to this model such as supersymmetry predict a value close to the experimental limits. By making more precise measurements, scientists hope to test these new theories.

Scientists try to measure the speedy electron's properties by attaching it to a bigger object, like a molecule. The JILA team focused on electrons associated with hafnium fluoride ions, so-called polar molecules with a positive charge at one end and a negative charge at the other end. Polar molecules can be trapped and manipulated with electric fields to remain in target states for 100 milliseconds, long enough for a precision measurement. The electric field inside the molecules is used to amplify the potential signal of eEDM.

JILA's new method involves rotating electric and magnetic fields fast enough to trap the molecular ions but slowly enough for the ions to be aligned with the electric field. The ions rotate in individual micro-circles while scientists measure their properties. The EDM is the difference between two magnetic energy levels. The method was developed in a collaboration between Cornell and JILA/NIST Fellow Jun Ye, who has conducted groundbreaking research with polar molecules.

The rotating field technique may be useful in quantum information experiments because a quantum bit could hold information for longer time periods in its electric and magnetic energy levels than in more commonly used quantum states. The ability to manipulate interactions of molecular ions might also simplify simulations of other spin-based quantum systems. In addition, the new technique might be used to investigate any variations over time in the fundamental "constants" of nature used in scientific calculations.