Nov 27 2013

How do you measure something that is invisible? It's a challenging task, but astronomers have made progress on one front: the study of dark matter and dark energy, two of the most mysterious substances in our cosmos.

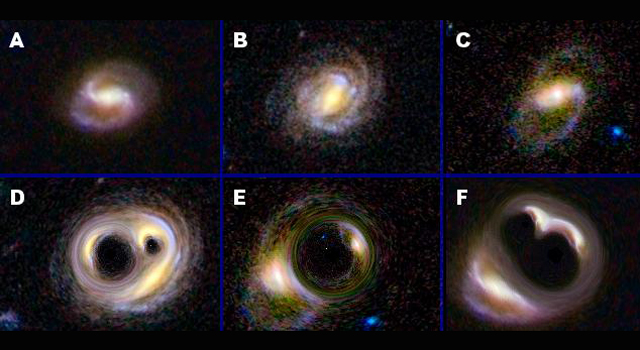

Can you match each galaxy in the top row with its warped counterpart in the bottom row? For example, is the warped version of galaxy A in box D, E, or F? Answer:A matches F; B matches D; and C matches E

Can you match each galaxy in the top row with its warped counterpart in the bottom row? For example, is the warped version of galaxy A in box D, E, or F? Answer:A matches F; B matches D; and C matches E

Dark matter is intermixed with normal matter, but it gives off no light, making it impossible to see. Dark energy is even more slippery, yet scientists think it works against gravity to pull our universe apart at the seams.

Now for the third time, an innovative competition has begun again with the goal of finding better tools for probing dark matter and dark energy. Called GREAT3, which stands for GRavitational lEnsing Accuracy Testing 3, the event is sponsored by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., and a European Union Network of Excellence called Pattern Analysis, Statistical Modeling and Computation Learning 2 (PASCAL2).

The idea behind the challenge is to spur scientists, including those from fields outside astronomy, to come up with new insight into the problems of measuring dark matter and dark energy. Contestants are asked to solve galaxy puzzles involving millions of images from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. A better understanding of the "dark side of the cosmos" may reveal new information about the very fabric and fate of our universe.

The first two challenges were a big success, attracting new brainpower to the field, including scientists from machine learning and particle physics. Machine learning involves programming computers to learn on their own using actual data from the real world. It has several applications, such as facial-recognition software, medical diagnostics and spam filtering, to name a few.

"Other data scientists have been thinking about the same type of algorithms we need for our cosmology tools for a long time," said Jason Rhodes of JPL. "We want to acquire that knowledge and see this field grow."

One of the most powerful tools for studying dark matter and dark energy is gravitational lensing. When dark matter lies between us and a distant galaxy, the light of the galaxy can be warped by the gravity from the dark matter. By measuring this warping, scientists can map dark matter, despite it being invisible. What's more, by looking at the distribution of dark and normal matter in our universe, scientists can get a better handle on dark energy and how it battles gravity to slow the growth of galactic structures.

In some cases of gravitational lensing, galaxies look wacky, as if seen in a funhouse mirror, or they appear multiple times. This is referred to as strong lensing. But in most cases, called weak lensing, the warping effects are tiny and impossible to see by eye.

The GREAT3 challenge is designed to improve methods for measuring weak lensing in preparation for future dark matter/dark energy missions, such as the European Space Agency's Euclid, in which NASA plays an important role, and the National Academy of Science's highest priority for NASA, WFIRST -- also known as the WFIRST-AFTA mission, which stands for Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope-Astrophysics Focused Telescope Assets.

The millions of images given to GREAT3 contestants show galaxies that have been artificially warped via weak lensing. The puzzle is to figure out precisely how the galaxy images were warped, a complex task that involves looking for patterns and sifting out artificial warping effects caused by telescope optics and the atmosphere.

The winner will be announced in May 2014 and will receive $3,000 worth of computing equipment, the perfect gift for programmers hoping to crack more cosmic codes.

"With these contests, we have seen new ideas seeping into our field," said Rachel Mandelbaum of Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, who is working with Rhodes and Barnaby Rowe of UCL (University College London), England, to organize the challenge, along with a special committee. "It's a fun problem to work on and it's a problem that needs to be solved."