Oct 5 2012

Scientists who study the ultra-small world of atoms know it is impossible to make certain simultaneous measurements, for example finding out both the location and momentum of an electron, with an arbitrarily high level of precision. Because measurements disturb the system, increased certainty in the first measurement leads to increased uncertainty in the second.

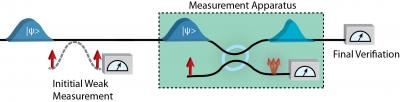

A general method for measuring the precision and disturbance of any system. The system is weakly measured before the measurement apparatus and then strongly measured afterwards. (credit: Lee Rozema, University of Toronto)

A general method for measuring the precision and disturbance of any system. The system is weakly measured before the measurement apparatus and then strongly measured afterwards. (credit: Lee Rozema, University of Toronto)

The mathematics of this unintuitive concept – a hallmark of quantum mechanics – were first formulated by the famous physicist Werner Heisenberg at the beginning of the 20th century and became known as the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. Heisenberg and other scientists later generalized the equations to capture an intrinsic uncertainty in the properties of quantum systems, regardless of measurements, but the uncertainty principle is sometimes still loosely applied to Heisenberg's original measurement-disturbance relationship. Now researchers from the University of Toronto have gathered the most direct experimental evidence that Heisenberg's original formulation is wrong. The results were published online in the journal Physical Review Letters last month and the researchers will present their findings for the first time at the Optical Society's (OSA) Annual Meeting, Frontiers in Optics (FiO), taking place in Rochester, N.Y. Oct. 14 -18.

The Toronto team set up an apparatus to measure the polarization of a pair of entangled photons. The different polarization states of a photon, like the location and momentum of an electron, are what are called complementary physical properties, meaning they are subject to the generalized Heisenberg uncertainty relationship. The researchers' main goal was to quantify how much the act of measuring the polarization disturbed the photons, which they did by observing the light particles both before and after the measurement. However, if the "before shot" disturbed the system, the "after shot" would be tainted.

The researchers found a way around this quantum mechanical Catch-22 by using techniques from quantum measurement theory to sneak non-disruptive peeks of the photons before their polarization was measured. "If you interact very weakly with your quantum particle, you won't disturb it very much," explained Lee Rozema, a Ph.D. candidate in quantum optics research at the University of Toronto, and lead author of the study. Weak interactions, however, can be like grainy photographs: they yield very little information about the particle. "If you take just a single measurement, there will be a lot of noise in that measurement," said Rozema. "But if you repeat the measurement many, many times, you can build up statistics and can look at the average."

By comparing thousands of "before" and "after" views of the photons, the researchers revealed that their precise measurements disturbed the system much less than predicted by the original Heisenberg formula. The team's results provide the first direct experimental evidence that a new measurement-disturbance relationship, mathematically computed by physicist Masanao Ozawa, at Nagoya University in Japan, in 2003, is more accurate.

"Precision quantum measurement is becoming a very important topic, especially in fields like quantum cryptography where we rely on the fact that measurement disturbs the system in order to transmit information securely," said Rozema. "In essence, our experiment shows that we are able to make more precise measurements and give less disturbance than we had previously thought."