Sep 18 2013

Astronomers have for the first time found a jet of high-energy particles from a dying star. The discovery, by a team including Chalmers scientists, is a crucial step in explaining how some of the most beautiful objects in space are formed – and what happens when stars like the sun reach the end of their lives.

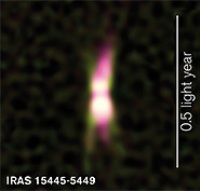

Two older objects, the Calabash nebula (a proto-planetary nebula) and M 2-9 (a young planetary nebula) show how IRAS 15445-5449 (left panel) may evolve in the future. The white bar indicates 0.5 light year. (Credits: E. Lagadec/ESO/A. Pérez Sánchez; NASA/ESA & Valentin Bujarrabal; B. Balick, V. Icke, G. Mellema and NASA/ESA)

Two older objects, the Calabash nebula (a proto-planetary nebula) and M 2-9 (a young planetary nebula) show how IRAS 15445-5449 (left panel) may evolve in the future. The white bar indicates 0.5 light year. (Credits: E. Lagadec/ESO/A. Pérez Sánchez; NASA/ESA & Valentin Bujarrabal; B. Balick, V. Icke, G. Mellema and NASA/ESA)

At the end of their lives, stars like the sun transform into some of the most beautiful objects in space: amazing symmetric clouds of gas called planetary nebulae. But how planetary nebulae get their strange shapes has long been a mystery to astronomers.

Chalmers University of Technology scientists have together with colleagues from Germany and Australia discovered what could be the key to the answer: a high-speed, magnetic jet from a dying star.

Using the CSIRO Australia Telescope Compact Array, an array of six 22-metre radio telescopes in New South Wales, Australia, they studied a star at the end of its life. The star, known as IRAS 15445−5449, is in the process of becoming a planetary nebula, and lies 23000 light years away in the southern constellation Triangulum Australe (the Southern Triangle).

“In our data we found the clear signature of a narrow and extremely energetic jet of a type which has never been seen before in an old, sun-like star”, says Andrés Pérez Sánchez, graduate student in astronomy at Bonn University, who led the study.

The strength of the radio waves of different frequencies from the star match the expected signature for a jet of high-energy particles which are, thanks to strong magnetic fields, accelerated up to speeds close to the speed of light.

Similar jets have been seen in many other types of astronomical object, from newborn stars to supermassive black holes.

“What we’re seeing is a powerful jet of particles spiralling through a strong magnetic field”, says Wouter Vlemmings, astronomer at Onsala Space Observatory, Chalmers. “Its brightness indicates that it’s in the process of creating a symmetric nebula around the star.”

Right now the star is going through a short but dramatic phase in its development, the scientists believe.

“The radio signal from the jet varies in a way that means that it may only last a few decades. Over the course of just a few hundred years the jet can determine how the nebula will look when it finally gets lit up by the star”, says team member Jessica Chapman, astronomer at CSIRO in Sydney, Australia.

The scientists don’t yet know enough, though, to say whether our sun will create a jet when it dies.

”The star may have an unseen companion – another star or large planet – that helps create the jet. With the help of other front-line radio telescopes, like ALMA, and future facilities like the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), we’ll be able to find out just which stars create jets like this one, and how they do it”, says Andrés Pérez Sánchez.

More about planetary nebulae

Seen in a small telescope, some planetary nebulae look like planets, hence the name. They are made of gas ejected from stars with similar mass to the sun at the end of their lives, glowing thanks to instense radiation from the star’s tiny but hot remaining core. The sun will become a red giant in a few billion years’ time, though at present it’s not clear whether it will then form a planetary nebula.

More about the research

The research is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, in the article A synchrotron jet from a post-asymptotic giant branch star.

The team consists of Andrés Pérez Sánchez (Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Bonn University, Germany), Wouter Vlemmings (Onsala Space Observatory at Chalmers University of Technology), Daniel Tafoya (Onsala Space Observatory at Chalmers University of Technology and UNAM, Morelia, Mexico) and Jessica Chapman (CSIRO, Australia).

The research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

More about the telescope

The CSIRO Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA), is a group of six radio-receiving dishes near Narrabri in New South Wales, Australia, that work together as one telescope. It is one of the most advanced telescopes of its kind. ATCA is run by CSIRO, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, which is Australia's national science agency.