Astronomers at the University of Arizona have discovered more about a surprisingly mature galaxy that existed at a time when the universe was only 2% of its present age, or less than 300 million years old. The study was published in Nature Astronomy.

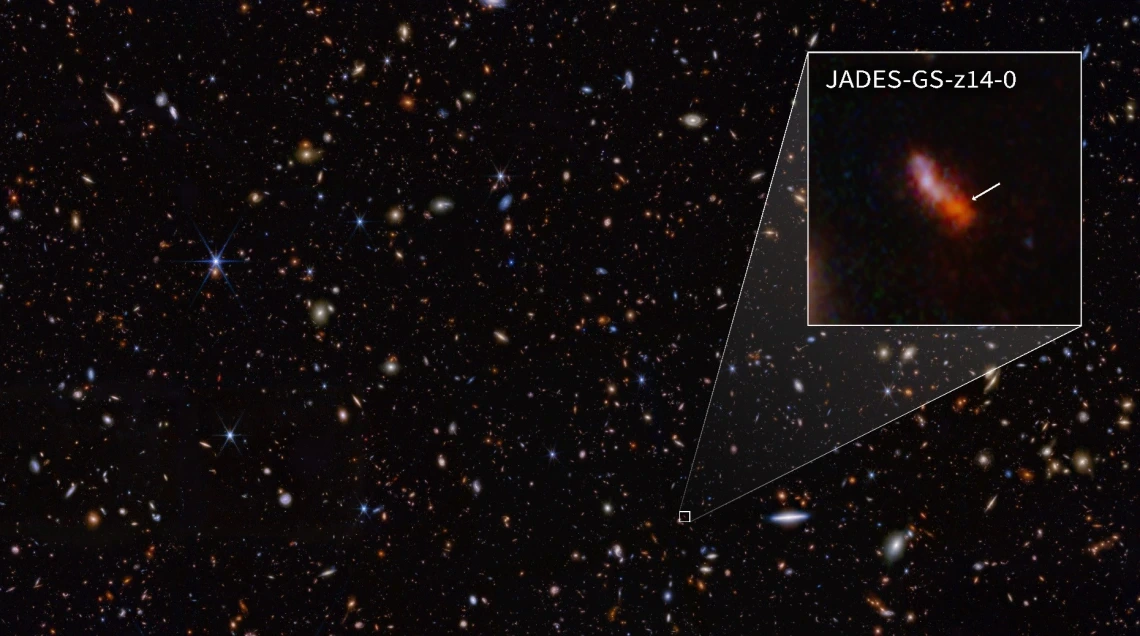

This infrared image from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope was taken by the onboard Near-Infrared Camera for the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, or JADES, program. The NIRCam data was used to determine which galaxies to study further with spectroscopic observations. One such galaxy, JADES-GS-z14-0 (shown in the pullout), was determined to be at a redshift of 14.3, making it the current record-holder for most distant known galaxy. This corresponds to a time less than 300 million years after the big bang. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Brant Robertson (UC Santa Cruz), Ben Johnson (CfA), Sandro Tacchella (Cambridge), Marcia Rieke (University of Arizona), Daniel Eisenstein (CfA), Phill Cargile (CfA)

The galaxy, named JADES-GS-z14-0, was observed by NASA's James Webb Space Telescope and, according to researchers, is unexpectedly bright and chemically complex for such an early cosmic era. This offers a unique look into the early history of the universe.

The study expanded on the researchers' earlier identification of JADES-GS-z14-0 as the most distant galaxy ever spotted, which was revealed in 2024. The new study explores the galaxy's chemical makeup and evolutionary stage in greater detail than the original discovery, which revealed the galaxy's record-breaking distance and surprising brightness.

The investigation was carried out as a component of the James Webb Space Telescope's Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, or JADES, a significant initiative aimed at studying distant galaxies.

Kevin Hainline, an Associate Research Professor at the U of A Steward Observatory and co-author of the new study, stated that this was more than just discovering something unexpected. This galaxy shattered the team's records in ways they hadn't anticipated; it was naturally bright and had a complex chemical makeup that was completely unexpected at such an early stage of the universe's history. The scan was purposefully designed to identify distant galaxies.

It's not just a tiny little nugget. It's bright and fairly extended for the age of the universe when we observed it.

Kevin Hainline, Associate Research Professor and Study Co-Author, Steward Observatory, University of Arizona

“The fact that we found this galaxy in a tiny region of the sky means that there should be more of these out there. If we looked at the whole sky, which we can't do with JWST, we would eventually find more of these extreme objects,” said Jakob Helton, a Graduate Researcher and Lead Study Author at Steward Observatory.

The research team made use of several pieces of equipment on JWST, including the Near Infrared Camera, or NIRCam, which was built under the direction of Marcia Rieke, a Professor of Astronomy at the University of A Regents. Significant levels of oxygen were discovered by the Mid-Infrared equipment, or MIRI, another telescope equipment.

Anything heavier than helium is referred to as a "metal" in astronomy, Helton stated. It takes generations of stars to develop such metals. Only hydrogen, helium, and minuscule amounts of lithium were present in the early universe. However, the JADES-GS-z14-0 galaxy's significant oxygen finding indicates that the galaxy may have been star-forming for up to 100 million years prior to its observation.

According to George Rieke, Regents Professor of Astronomy and the study's senior author, the galaxy must have formed a generation of stars very early on to produce oxygen. For oxygen to be released into interstellar space—where new stars would form and evolve—those stars first had to go through their life cycles and explode as supernovae.

It's a very complicated cycle to get as much oxygen as this galaxy has. So, it is genuinely mind boggling.

George Rieke, Regents Professor and Study Senior Author, Astronomy, University of Arizona

The discovery pushes back the timetable for when the first galaxies could have formed following the Big Bang by indicating that star formation started far earlier than previously believed.

About nine days of telescope time were needed for the observation, which involved focusing on a minuscule area of the sky for 167 hours of NIRCam and 43 hours of MIRI imaging.

This galaxy was fortunate to be in the ideal location for the U of A researchers to use MIRI to observe it. According to Helton, they would not have obtained this important mid-infrared data if they had angled the telescope even a fraction of a degree in any way.

“Imagine a grain of sand at the end of your arm. You see how large it is on the sky – that's how large we looked at,” said Helton.

A strong test case for theoretical models of galaxy formation is the presence of such a developed galaxy at such an early stage of cosmic history.

“Our involvement here is a product of the U of A leading in infrared astronomy since the mid-'60s, when it first started. We had the first major infrared astronomy group over in the Lunar and Planetary lab, with Gerard Kuiper, Frank Low, and Harold Johnson,” said Rieke.

By directly observing and studying galaxies from the early universe, we may gain valuable insights into how the cosmos evolved from simple atoms to the complex chemistry necessary for life as we know it.

“We're in an incredible time in astronomy history. We're able to understand galaxies that are well beyond anything humans have ever found and see them in many different ways and really understand them. That's really magic,” said Hainline.

The study was partially funded by the European Research Council Advanced Grant 789056 "FirstGalaxies," NASA grants NAS5-02105 and NNX13AD82G to the University of Arizona, and ERC Advanced Grant 695671 "QUENCH." The Science and Technology Facilities Council, the National Science Foundation, the Royal Society, the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, the UKRI Frontier Research project "RISEandFALL," and others contributed additional funds.

Journal Reference:

Helton, M. J., et al. (2025) Photometric detection at 7.7 μm of a galaxy beyond redshift 14 with JWST/MIRI. Nature Astronomy. doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02503-z