Astronomers from the University of Arizona have used NASA’s Hubble and James Webb space telescopes to capture unprecedented details of the extensive debris disk encircling Vega, one of the brightest stars in the night sky.

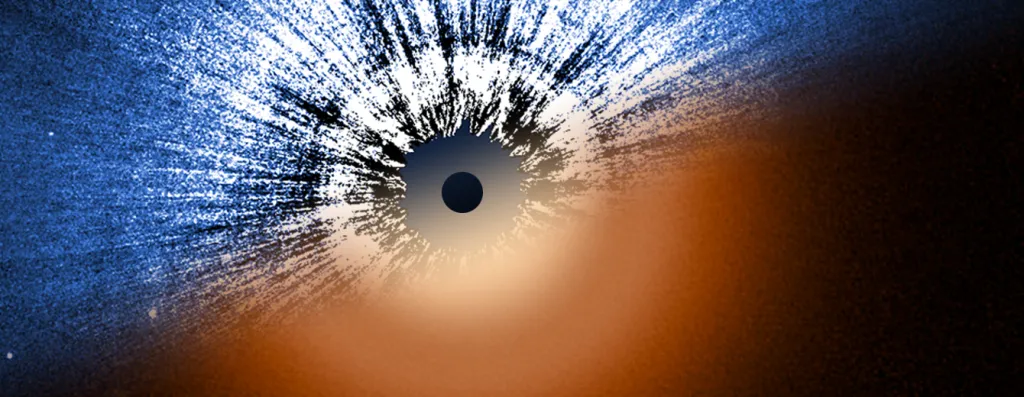

Teams of astronomers used the combined power of NASA's Hubble and James Webb space telescopes to revisit the legendary Vega disk. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, S. Wolff (University of Arizona), K. Su (University of Arizona), A. Gáspár (University of Arizona)

Teams of astronomers used the combined power of NASA's Hubble and James Webb space telescopes to revisit the legendary Vega disk. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, S. Wolff (University of Arizona), K. Su (University of Arizona), A. Gáspár (University of Arizona)

Using the combined capabilities of NASA's Hubble and James Webb space telescopes, teams of astronomers revisited the legendary Vega disk. This immense structure spans roughly 100 billion miles and offers new insights into planetary formation and star systems beyond our own, as recently published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Between the Hubble and Webb telescopes, you get this very clear view of Vega. It is a mysterious system because it is unlike other circumstellar disks we have looked at. The Vega disk is smooth, ridiculously smooth.

Andras Gáspár, Associate Astronomer, The University of Arizona

To the researchers’ surprise, they found no evidence of large planets disturbing the face-on disk, as one might expect with planets carving paths through the dust like snowplows.

It is making us rethink the range and variety among exoplanet systems.

Kate Su, Study Lead Author, University of Arizona

The James Webb Space Telescope detected warm infrared emissions from sand-sized particles in a swirling disk around Vega, a blue-white star shining 40 times brighter than our Sun. Meanwhile, the Hubble Space Telescope captured an outer halo within this disk, composed of finer, smoke-like particles that reflect Vega's intense starlight.

This layered dust distribution results from the effects of starlight pressure, with smaller grains pushed outward faster than larger grains, creating distinct zones based on particle size and distance from the star.

Different types of physics will locate different-sized particles at different locations. The fact that we're seeing dust particle sizes sorted out can help us understand the underlying dynamics in circumstellar disks.

Schuyler Wolff, Study Lead Author, University of Arizona

Observations revealed a subtle gap in Vega's debris disk, approximately 60 astronomical units (AU) from the star, twice the distance of Neptune from the Sun. Beyond this gap, the disk remains remarkably smooth, extending inward until obscured by Vega’s glare. This smoothness suggests the absence of planets with masses comparable to Neptune in wide orbits, contrasting with our solar system's structure.

Su added, “We are seeing in detail how much variety there is among circumstellar disks, and how that variety is tied into the underlying planetary systems. We are finding a lot out about the planetary systems — even when we can’t see what might be hidden planets. There's still a lot of unknowns in the planet-formation process, and I think these new observations of Vega are going to help constrain models of planet formation.”

Disk Diversity

Young stars accrete material from surrounding disks of gas and dust, remnants of the clouds from which they formed. In the mid-1990s, the Hubble Space Telescope observed disks around many developing stars, sites where planets form, migrate, and sometimes even disintegrate.

For mature stars like Vega, approximately 450 million years old (our Sun is about ten times older), dusty disks continue to accumulate material from asteroid collisions and cometary debris. Within our solar system, minor bodies replenish dust—seen as Zodiacal light—at around 10 tons per second. Planetary forces direct this dust, allowing astronomers to detect distant planets by observing their gravitational effects on surrounding dust.

"Vega continues to be unusual," said Wolff. "The architecture of the Vega system is markedly different from our own solar system where giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn are keeping the dust from spreading the way it does with Vega."

For comparison, the nearby star Fomalhaut shares similar distance, age, and temperature with Vega, but its circumstellar structure is vastly different, featuring three nested debris belts. Scientists hypothesize that planets act as shepherds around Fomalhaut, gravitationally shaping its dust into rings, though no planets have been definitively observed there yet.

Team member George Rieke of the University of Arizona, a member of the research team, added, “Given the physical similarity between the stars of Vega and Fomalhaut, why does Fomalhaut seem to have been able to form planets and Vega didn't?”

“What's the difference? Did the circumstellar environment, or the star itself, create that difference? What's puzzling is that the same physics is at work in both,” Wolff stated.

First Clue to Possible Planetary Construction Yards

Vega, located in the summer constellation Lyra, is among the brightest stars in the northern sky. It holds a special place in astronomy, as it provided the first observational hint of material orbiting a star—potentially the building blocks for planets and possibly life. This concept was initially suggested by Immanuel Kant in 1775, but actual observational evidence didn’t emerge until 1984 when NASA’s Infrared Astronomy Satellite (IRAS) detected an unusual excess of infrared light from warm dust around Vega. This was interpreted as a disk or shell of dust extending twice as far as Pluto’s orbit would be from the star.

In 2005, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope mapped a dust ring around Vega, with additional observations from submillimeter telescopes like Caltech's Submillimeter Observatory in Hawaii, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, and ESA’s Herschel Space Telescope confirming its presence. However, these telescopes could not capture finer details of the structure.

Rieke stated, “The Hubble and Webb observations together provide so much more detail that they are telling us something completely new about the Vega system that nobody knew before.”