Researchers from Georgia State University's Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) Array have uncovered new details about the dimensions and appearance of the North Star, also known as Polaris. Their findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal.

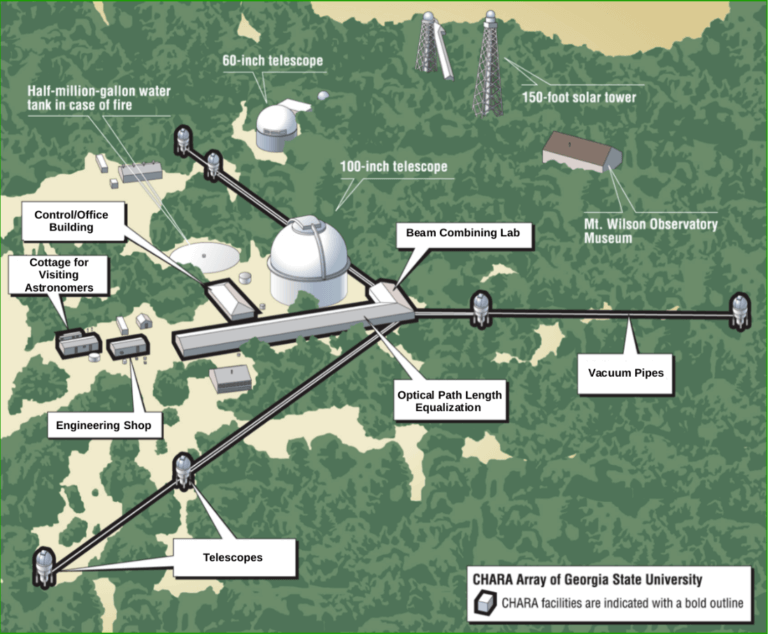

The CHARA Array is located at the Mount Wilson Observatory in the San Gabriel Mountains of southern California. The six telescopes of the CHARA Array are arranged along three arms. The light from each telescope is transported through vacuum pipes to the central beam combining lab. All the beams converge on the MIRC-X camera in the lab. Image Credit: Georgia State University

The North Star, Polaris, is a crucial landmark in the night sky, guiding travelers for centuries. Not only is it a reliable navigation tool, but it is also a star with some fascinating traits of its own. Polaris is the brightest member of a triple-star system and shines as a pulsating variable star, which means its brightness changes periodically as its diameter expands and contracts over a four-day cycle.

Polaris is classified as a Cepheid variable, a type of star that astronomers use as a "standard candle" to measure cosmic distances. The pulsation period of these stars is directly linked to their true brightness: brighter Cepheids pulse more slowly. By comparing how bright a Cepheid appears from Earth to its known brightness, astronomers can calculate how far away it is, which helps us understand the scale of the universe and its rate of expansion.

Recently, a team led by Nancy Evans at the Center for Astrophysics took a closer look at Polaris using the CHARA optical interferometric array at Mount Wilson, California. Their goal was to map the orbit of a faint companion star that circles Polaris every 30 years. This detailed study helps us learn more about the complex dynamics of this iconic star system.

The small separation and large contrast in brightness between the two stars makes it extremely challenging to resolve the binary system during their closest approach.

Nancy Evans, Center for Astrophysics, Georgia State University

The CHARA Array, located at the historic Mount Wilson Observatory, merges the light from six telescopes spread across the mountaintop. This combined light acts like a giant 330-meter telescope, allowing it to detect even the faintest companion star as it passes close to Polaris. The observations were captured using the MIRC-X camera, developed by astronomers at the University of Michigan and Exeter University in the U.K., known for its exceptional ability to reveal details of stellar surfaces.

With this setup, the team successfully tracked the orbit of Polaris's faint companion and observed changes in the Cepheid's size as it pulsated. They discovered that Polaris has a mass five times greater than the Sun and a diameter 46 times larger.

The most exciting finding was the close-up images of Polaris, which provided the first detailed view of a Cepheid variable's surface. These observations offer a groundbreaking glimpse into the appearance of these fascinating stars.

“The CHARA images revealed large bright and dark spots on the surface of Polaris that changed over time,” Gail Schaefer, Director of the CHARA Array, said.

The presence of spots and the rotation of the star might be linked to a 120-day variation in measured velocity.

We plan to continue imaging Polaris in the future. We hope to better understand the mechanism that generates the spots on the surface of Polaris.

John Monnier, Professor, Astronomy, University of Michigan

The new observations of Polaris were part of the open access program at the CHARA Array. This program allows astronomers from around the globe to apply for observation time through the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory (NOIRLab).

Journal Reference:

Evans, R. N., et al. (2024) The Orbit and Dynamical Mass of Polaris: Observations with the CHARA Array. The Astrophysical Journal. doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ad5e7a.