Meteorites are asteroid fragments that arrive on Earth like shooting stars. These cosmic deposits have preserved the primordial soup from which our solar system arose, preserving it like a time capsule. These rocks assist researchers in understanding the origins of matter and life on Earth. Dr Christian Vollmer from Münster University’s Institute of Mineralogy, in collaboration with British colleagues, analyzed one of these time capsules, the Winchcombe meteorite.

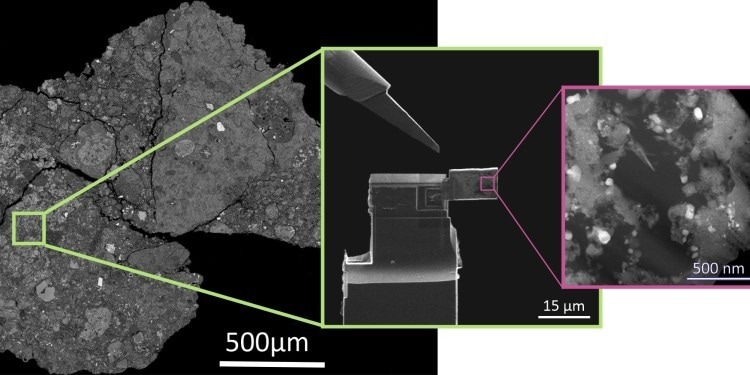

Using a nanomanipulator and an ultra-fine ion beam, a tiny lamella, about five by ten micrometers in size and only one hundred nanometers thin, is cut out of the meteorite and attached to a sample bar. The scientists can then analyze the organic particles in this lamella under an electron microscope (right). Image Credit: SuperSTEM Laboratory, Daresbury, UK

Using a nanomanipulator and an ultra-fine ion beam, a tiny lamella, about five by ten micrometers in size and only one hundred nanometers thin, is cut out of the meteorite and attached to a sample bar. The scientists can then analyze the organic particles in this lamella under an electron microscope (right). Image Credit: SuperSTEM Laboratory, Daresbury, UK

The researchers are now the first to establish, with great accuracy, the presence of certain significant nitrogen compounds in this meteorite, including amino acids and heterocyclic hydrocarbons, without the use of any chemical treatment and using a novel detector design. The results were reported in the journal Nature Communications.

Background

The Winchcombe meteorite was discovered by a camera network in England in February 2021 and collected within a few days.

Normally, meteorites are tracked down in the cold and hot deserts on Earth, where the dry climate means that they don’t weather very fast, but they do change as a result of humidity. If a meteorite fall is observed soon after the event and the meteorite is quickly collected, as was the case in Winchcombe, they are important ‘witnesses’ for us regarding the birth of our solar system – which makes them especially interesting for research purposes.

Dr. Christian Vollmer, Institute of Mineralogy, Münster University

The beginnings of life on Earth are still unknown, although some experts believe that the first biologically relevant stuff arrived in meteorites around four billion years ago. This category comprises complex organic substances such as amino acids and hydrocarbons. However, these compounds have extremely low quantities, and scientists must often extract them from the meteorite using solvents or acids before enriching them for analytical reasons.

Without first subjecting the Winchcombe meteorite to chemical treatment, Christian Vollmer’s team could show the presence of these physiologically significant nitrogen compounds, albeit at extremely low amounts. A contemporary, high-resolution electron microscope, like the one used by the researchers, is only available in a small number of places globally.

This “super-microscope” at the SuperSTEM laboratory in Daresbury, England, is capable of chemically analyzing the materials using a novel kind of detector and providing an atomic-resolution image of high-carbon compounds.

“Demonstrating the existence of these biologically relevant organic compounds in an untreated meteorite is a significant achievement for research. It shows that these building blocks of life can be characterized in these cosmic sediments even without chemical extraction,” Vollmer added.

The likelihood of these delicate compounds changing during chemical treatment makes the development even more crucial. Because of this, research on small, extraterrestrial specimens returned to Earth from space missions, like the dust particles from asteroids recently returned by NASA (OSIRIS-REx) and the Japanese Space Agency (Hayabusa2), could profit from the analytical techniques used here with solid matter.

The German Research Foundation provided financial assistance for this work as part of the SPP1833 Priority Program, “Building a Habitable Earth.”

Journal Reference:

Vollmer, C., et. al. (2024) High-spatial resolution functional chemistry of nitrogen compounds in the observed UK meteorite fall Winchcombe. Nature Communications. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-45064-x